Tour of Tiananmen

At the heart of Beijing lies Tiananmen Square, a desolate, imposing expanse that acts as the foreboding backdrop to the Forbidden City - come with me for a walk around it

Beijing revolves around the Forbidden City like a spinning top around its axis, the capital’s concentric ring roads drawing ever closer until, finally, they encircle the vast, featureless plateau that is Tiananmen Square. A representation of man’s desire to impose upon nature, this desolate patch of concrete is where many visitors to China begin their journey, one that leads to the Middle Kingdom’s past, present and future.

Meaning the ‘Gate of Heavenly Peace’, the foreboding square takes its name from the entranceway to the Forbidden City, which lies at its northern edge. Measuring 880 by 500 meters, it is the largest, urban square in the world and, in recent historical eyes, is entwined with the tragic events of June 4, 1989. However, the history of Tiananmen stretches much further back than mere decades, with its origins 600 years in the past.

First constructed under the Ming dynasty in 1417, the area later underwent renovation work in 1699 during the early Qing period, and for a long time was declared off limits to commoners, instead occupied by offices of imperial ministries. Following the Boxer Rebellion of 1899-1901 – an uprising against foreign influence that saw the deaths of many Chinese Christians and foreigners, and the subsequent occupation of Beijing by 20,000 foreign troops – the buildings occupying Tiananmen suffered heavy damage and were eventually demolished, laying the foundations for the square we know today.

At the square’s very center once lay one of China’s most important gates. First known as the Great Ming Gate, then the Great Qing Gate, as dynasties changed, it was finally labeled the ‘Gate of China’. This ceremonial structure performed a symbolic role much akin to Mumbai’s famed Gateway of India, and remained closed to all except for the Emperor. Commoners wishing to pass through the area were diverted to either side of the gate, and over the years a narrow, bustling network of lanes formed known as the ‘Chess grid Streets’. This hubbub of commerce remained in situ for hundreds of years until post 1949, when the newly formed government of the People’s Republic of China deemed it, and the gate, symbols of a weak past, and sadly demolished them (along with the city walls, which were turned into ring roads - there are seven and counting).

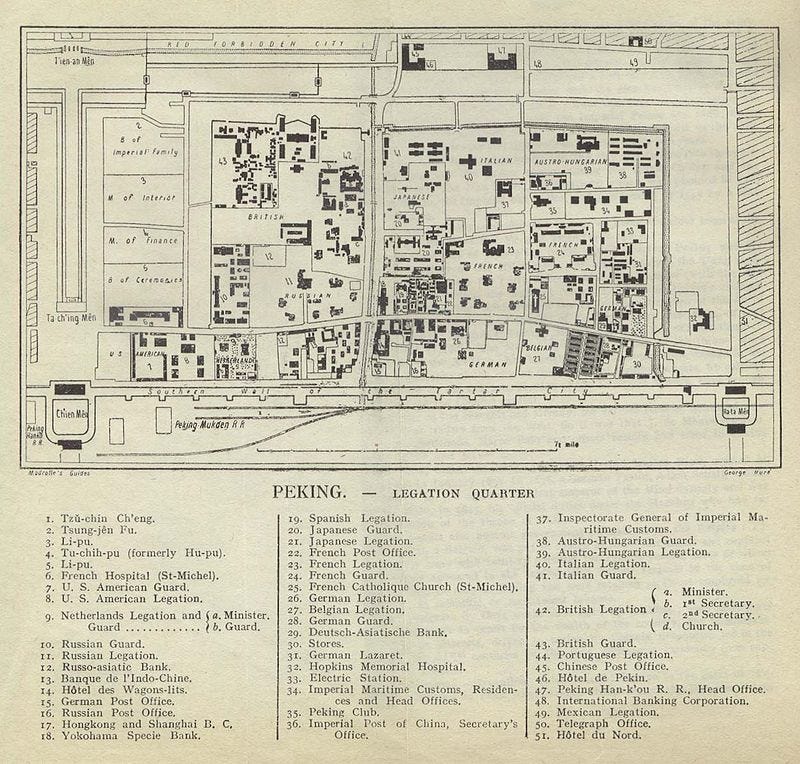

With the 1950s expansion southwards, came the addition of the iconic, and imposing, structures one sees today. Stepping onto the square from the south, visitors first encounter the imperial era Zhengyangmen (colloquially now known as Qianmen – front gate). To its direct east stands the former Peking Railway Station, one of many remaining examples in the area of western influenced architecture. Indeed, the land to the east of the station was formerly known as the Legation Quarter, an area occupied by a multinational population full of intrigue (read my interview with Paul French).

Heading due north from the gate, it is hard not be awed by the imposing edifice that lies straight ahead (which, one would assume was deliberately made more daunting than the area’s remaining old imperial structures). This is the final resting place of Mao Zedong; revolutionary, communist icon, and founder of the People’s Republic of China. Formally known as the Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, it is commonly referred to as the Mao Mausoleum, and contains the last remains of the ‘Great Helmsman’.

Despite his wishes to be cremated, upon his death Mao’s body was instead embalmed in the Communist fashion (as were Lenin and Ho Chi Minh), preserving his likeness for posterity. With its construction beginning in the immediate aftermath of his death on 9 September 1976, the mausoleum was completed by the following May. As local officials lacked the skills to treat the corpse, they were forced to learn the technique from the Vietnamese, who had entombed their own founding leader the year before (interestingly, he also had asked for cremation). Literally lined with symbolism, the tomb was constructed using material from the breadth of China (including rock from Qomolangma – we know it as Mount Everest – and sand dug from the Taiwan straits).

In front of Mao’s final resting place is the only other structure on Tiananmen Square itself, the Monument to the People’s Heroes. Rising up to a height of almost 38 meters tall, the obelisk was built in 1958, and stands directly between the Great Hall of the People (China’s parliament building) and the National Museum of China, (which run along the square’s western and eastern edges, respectively). Carved into the pedestal at its base are eight bas-reliefs, which tell the story of the nation’s long, revolutionary struggle; from the Opium War of 1840 (a conflict which eventually led to the ceding of Hong Kong to the British), to the War of Resistance Against Japan begun in 1931, and eventually to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1945. While it is all unashamed communist propaganda, these carvings do provide an insight into the long struggle by the Chinese to establish an independent and powerful Middle Kingdom.

From here, it is a just a swift walk to the northernmost edge of the square, passing the visiting locals (who on occasion are allowed to fly kites here), and always under the watchful eye of the omnipresent policeman and security cameras. If you follow the steady stream of tourists heading underground, and traverse the passageway to the other side of the road, you emerge at the heavenly gate itself. Most pause here to take a photo underneath the foreboding portrait of Mao (interestingly, his arch rival Chiang Kai-shek beat him to it before his defeat in 1949), before heading through the giant gates, and walking into the Forbidden City, once home to the emperors of China.

This sacred residence, made globally famous in Bernardo Bertolucci’s exquisite 1987 movie The Last Emperor, is the ideal setting for a lazy afternoon’s wandering, a lesson in ancient history following the totalitarian tones of Tiananmen Square. Before you enter the complex, the smart traveler pays a little extra to pick up an English-language audio tour. Narrated by Roger Moore (at least, it was when I last visited), the smooth, dulcet tones of the former 007 are the classiest way to explore Puyi’s former home (certainly the most soothing) – and your perfect companion for the journey ahead.

Note: In recent years advance bookings have been required to visit the square, which is now cordoned off by a series of gates and fences. Sadly, the days when you could just wander on (or, as I did my first time, get a friendly taxi driver to drop me off at the side) are long gone.

I walked around Tiananmen Square in 2018. Unfortunately, my memories of where I was, what I was doing and how I felt when I heard “the tragic news” of events that took place there, pressed in closely to and over me as I wandered in the Square. They were an omnipresence that I couldn’t shake and I was unable to breathe and be in the now. Too much heartache for so many.