The French Connection

Meet Paul French, celebrated author of books about the days of old China, including the new 'Her Lotus Year', about the Duchess of Windsor's 1920s Shanghai sojourn

Hi Paul. How’s life in London? Do you ever miss China?

I’m London born-and-bred, my family are all in North London or various South Coast towns where Londoners inevitably decamp eventually to see out their days, so there was a good welcoming world to drop back into when I came back some 10 years ago.

I basically read, write, watch TV and occasionally garden. I miss China sometimes, though now exist predominantly in the China that’s inside my head, and the China I’m researching at any given time.

I was never massively interested in contemporary China to be honest, that was the day job. I remember the (now sadly gone) Lynn Pan, a great writer on China, being asked if she read the newspapers on China and what she thought? ‘Yes’, she replied, ‘but only those published between 1932 and 1937.’ I seem to be stuck in a similar groove.

What brought you out to live in China in the first place?

I studied Chinese history and then fell into market research with some other Chinese graduates and we saw an opportunity in 1990s Shanghai. I set up a Rep Office (if they still have those?) and we just started writing reports for companies, banks, embassies, trade bodies, whoever was interested, on retailing and consumption in China.

It was a good way to wander around and see the country - out to city ‘Tier Whatever’ at the end of the line. You could write about coal mining or shipbuilding (both massive at the time), but you’ve seen one coal mine or shipyard and you’ve seen them all really. Retail and consumer was not a story then, many thought it never would be - China would just make, not consume. But we got lucky and China went shopping mad and everyone wanted the data we were gathering.

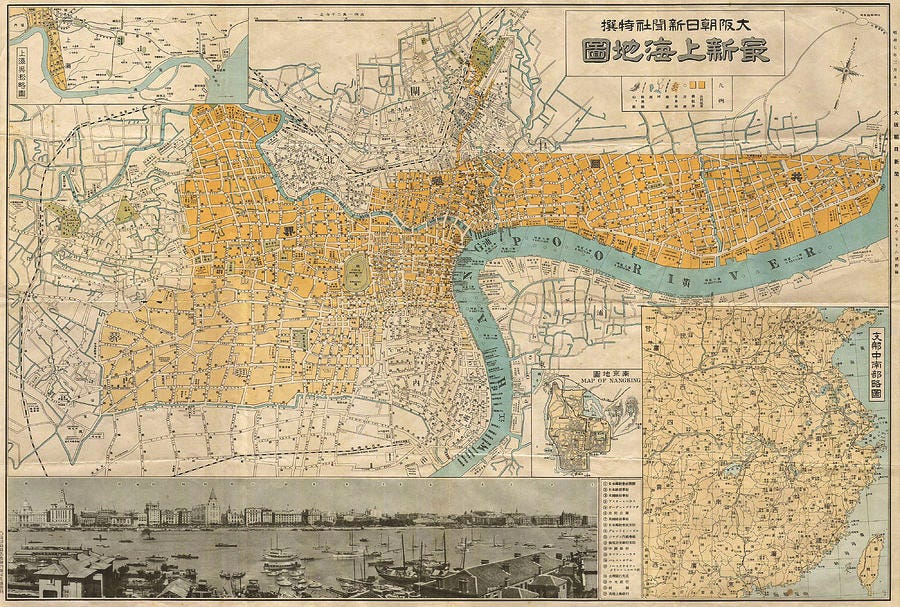

I always lived in Shanghai. It had everything I wanted from a city - an exciting history, the ability to walk most places you needed to go, decent public transport, good restaurants, and a river running through it. I’ve spent so much time in Peking, but though fascinated, never came to really love it; similarly so Guangzhou, Hong Kong and the south. Neither quite worked for me, but Jiangnan region did - Shanghai, but also Suzhou, Hangzhou, Nanjing, Ningbo (though I always wish I’d upped and gone to live in Macao’s old town in a charming flat above a pastel de nata shop - ahh regrets!).

After first visiting China in the early ‘90s, you left in 2014 following the release of your breakout book Midnight in Peking in 2011. Looking back, how was that time for you?

I never had a plan in mind for China. I just assumed one day we’d go bankrupt and sheepishly leave at midnight, or the authorities would kick us out, or something else would come along. But we stayed liquid, under the radar and then eventually around 2012 a big British market research company came along and offered to buy us.

We hadn't been up for sale - we had no idea what to do if we sold, but the offer was decent and we all had other lives we wanted to pursue. I got locked in for a couple of years as you do in these acquisitions and then split remembering that corporate life wasn’t really for me (to be honest the corporation didn’t think I was really for them either).

So everything collided - selling a business, ageing parents (which inevitably comes along and has to be dealt with) and Midnight in Peking doing pretty well. It was a busy time, but when you get lucky and the stars align you’ve got to grab it and run with it for all it’s worth.

Just briefly on Midnight, what drew you to the mystery of the tragic 1937 death of expat Pamela Werner in Beijing?

I’d been writing in the evenings and weekends, did a couple of obscure Shanghai history books - labours of love - but thought it would be fun to see if I could find a story (and then write it well enough) to reach a bigger, international audience of readers with a China tale. When I dug into Pamela Werner’s unsolved 1937 murder I found a lot of documents and details that had been stuffed away in archives for years.

At the time, the Japanese invasion of China doomed the case to failure. Then the war, the civil war, the revolution. She was forgotten. It really was the end of an old China and the start of a new one and Pamela’s story didn’t carry over. I thought it was a good tale, that I could perhaps write it well, and that the sense of justice never being done was palpable and would appeal to a big audience. Her story also took me into the hutongs and alleys of Peking in the 1930s, which was right where I wanted to be.

I have to say that Jo Lusby who ran Penguin China back then championed the book and took it around Penguin globally - the UK, US, Australia and India all bought it, and suddenly we had a big book on our hands. It really was one of those throwaway plans cooked up over a few tepid merlots (largely in the late, greatly missed Bookworm down on south Sanlitun) that snowballed and turned out brilliantly.

I hear there is a movie version possibly in the works?

I can say that a seriously big Chinese movie director has the rights and has been scribbling away and storyboarding for some time, all through Covid, and is still. Hopefully one day he’ll pull it off.

The Chinese language edition of the book has done well. It sells and sells, so there’s still anticipation. I’d like it to be done by a Chinese director and team for a global audience. It’s been fun being a best-selling author in China with a book about China and getting a really positive response from local readers and reviewers. Now I’d like to eventually have a nice big film of the book that could be a hit Chinese movie and be seen around the world too.

My book on Shanghai gangsters - City of Devils - is also being worked on by a team in Los Angeles. They’re equally keen, and I like them too. Seeing the different ways Hollywood and Beijing work is quite fascinating. Strangely perhaps there’s less individualism in Hollywood than China, where there’s more of an auteur style. Movies and TV seem to my experience to be more of a team sport in the US than the PRC - not sure what that observation tells you?

Moving on - you have a new book coming out in November. Tell me about Her Lotus Year.

Her Lotus Year is about the one year that the American Wallis Simpson, later Duchess of Windsor (after King Edward VIII famously abdicated to marry her) spent in China (1924 to 1925). It just happens to be an incredible year in China’s history - strikes and labour strife, warlord fighting, Puyi expelled from the Forbidden City, massive disease outbreaks, Dr Sun Yat-sen dying, a China divided between north and south, warlord and republican. And I think, given how difficult Chinese history can be for western readers who don’t get much or any at school, seeing all this through the eyes of a western sojourner and her own experiences in China at the time is interesting.

Of course it also sheds a light on Wallis’s later life - China was where she became cosmopolitan, more sophisticated and developed her lifelong style (the qipao style dresses, chignon hairstyle, jade jewellery etc) that attracted the Prince of Wales. For ordinary readers drawn to the book for Wallis, it is a time in her life that has not been written about much - royal biographers tend to be hopeless Sinologists (hopefully this isn’t true the other way round!).

By the way I’m happy the book is coming out in November, exactly 100 years after Wallis first arrived in Asia, got off a boat in Hong Kong in November 1924 and found a flat in Kowloon.

How did you come to be so interested in her China sojourn?

Well, let’s be frank - there are rumours about Wallis’s time in China - rather salacious and naughty ones - that she had many lovers, could turn a rather particular sexual trick, that she smoked opium, that she worked for gambling rings, that she posed for pornographic photographs. At the time of the abdication in 1936 a supposed “China Dossier” was circulated by the British government to the Establishment blackening Wallis’s character and blaming all on her supposedly immoral time in China (with not a little misogyny and Sinophobic ‘Yellow Peril’ thrown in). I thought we should get to the bottom of that….

Where did you find the most unexpected information?

I simply did my best to follow her footsteps from the moment she arrived in Hong Kong to the moment she left Peking about a year later. I knew that none of the more sensational allegations against Wallis in the “China Dossier” were true - it was fake news - but I didn’t realise that the intelligence services had been quite clever. All the stories were true of someone, so those stories had to be uncovered of course.

I also didn’t realise that she had gone to Hong Kong to try and repair her first marriage - to Win Spencer, a US naval officer who had been posted to the territory. He was a drunk, a bully and abusive. She finally had enough and fled to Shanghai, hoping to get a divorce. That wasn’t possible so she moved on to Peking. But it was a crazy time - labour fighting in Guangzhou, warlord battles around Shanghai, a typhoid epidemic in Tianjin and more warlord fighting in Peking. I also think she was moving around couriering documents for the US government as the train lines, telegraph lines etc were all disrupted. It’s the only way to explain her slightly inexplicable itinerary at the time.

She's a controversial character, at least in British eyes. Do you think your book might help change her reputation?

Maybe - she’s been “That Woman” to the British public now for nearly 90 years. The tabloids still run stories about her every so often that highlight (the unfounded, as I show in the book) stories about her. In 1936, when she heard them, Wallis apparently declared them ‘Venom, venom, VENOM…’ but she couldn't do anything about it.

In her memoir, The Heart Has Its Reasons (published in the 1950s) she remembers her China year as her ‘Lotus Year’, after Homer’s soporific stranded mariners who never want to return home, and thinks fondly of her time spent in Shanghai and Peking.

I hope people will come to the book with an open mind and see that before she was the Duchess, she had been a physically, emotionally and verbally abused woman, one who had struck out independently to travel across China at an incredible time and when few single European women did such a thing. It was part of the process of her becoming a woman a King would find fascinating and, ultimately, give up a crown and an empire for - which is a pretty big deal!

I think Americans perhaps see her rather differently and may respond differently too. She was a Baltimore girl who’s been maligned in the British press for decades. I’m hoping they’ll think they can recover her somewhat from a bad history.

Of course later she perhaps wasn’t all perfect, and the Duke and Duchess did flirt with fascism and were somewhat self-centred and greedy. But that was all later, after the abdication, World War Two, and when they were in exile. This is Wallis in her twenties and a very different woman.

I’m happy that my Chinese publisher jumped at the book too, as I really have no idea what the average Chinese reader thinks of Wallis. But I do know that the Chinese audience loves the idea of China and China's story being at the centre of other massive stories - such as the abdication. We saw that with the success of The Six, the documentary that focused on the Chinese survivors of the Titanic. So many Chinese readers knew the story of the Titanic (and the movie of course), like many know the story of the abdication, but never knew the Chinese angles on these stories.

What do you think was it about Shanghai in the 1920s and '30s that attracted such expat adventurers like Wallis?

Well there’s a simple answer - the ocean liners all went there, and there was a lot of money to be made with hardly any constraints or rules.

But what interests me most is that Shanghai was this slightly odd, semi-colonial place of extraterritoriality. It was certainly ripped from China by violence in the wake of the First Opium War and a very “unequal” treaty. Yet, Shanghai became a place of opportunity and sanctuary - for all those ‘White Russians’ fleeing the Bolsheviks, 25,000 Jewish refugees from Europe leading up to WWII, as well as numerous Chinese fleeing endemic poverty, disease, corruption, the Taiping, warlords, whatever, to seek their fortune in Shanghai.

It’s also a port city and port cities are always the most exciting - London, New York, Marseille, Rio, etc. They are where people meet, swap ideas, fall in love with people from far away places and (I know it’s a bit unfashionable these days with some) inter-mix cultures to create new hybrids of literature, music, architecture, film, technology, fashion and language. Shanghai is all that… and something more in being a refuge from the chaos of China for a century from the mid-1800s to 1940 or thereabouts.

Of course while many came for sanctuary, safety, to make their fortunes in a variety of entrepreneurial ways, Shanghai - the original sin city - did also attract the grifters, gangsters and ne'er-do-wells - they fascinate me too of course, hence City of Devils.

We both also lived in Shanghai at a time of openness that saw an influx of foreigners. Are there any parallels that can be drawn between the Shanghai of the 1930s and 2000s?

I’m wary of that (and with this new book, parallels between Wallis and Meghan too!). I don’t think the foreigners of the 1990s and early 2000s were very important or made much of a dent on the country ultimately (whatever they may think themselves in their more vainglorious moments down the pub) - though most, I hope, had fun setting up businesses and living a rather sybaritic lifestyle in a way that’s perhaps not so possible now. The grey zones were massive and legion then, for everyone.

If there are parallels to be found, then it was in the renewed ability of Chinese people to move about, slip the restrictions of the old Maoist state and make themselves anew in Shanghai. Of course hukou regulations and all that nonsense existed, previous generations of Shanghainese were rude and dismissive of the internal migrants in the ‘90s, discrimination was rife, but a lot of what got done in that time - construction, the boom in services - was down to those people. And many of them not only managed to survive but thrived, seriously well in some cases.

I’m sure we all know people who came to Shanghai (perhaps via college, or work, or whatever from the interior) who went on to be super successful because they had a good idea. A few foreigners did too. But foreigners were always a minority in 1926 and 1936 as much as in 1996 or 2006 - it was the Chinese who came to Shanghai (just as they did in the 1860s through to the 1930s) who really did the hard work and, in many cases, reaped the major benefits - and deservedly so.

Nobody much cared who came to Shanghai for the near-century of the old treaty port. Then in the 1990s and early 2000s everything was fungible again for a while. From the 1950s to the later 1980s Shanghai was static and so closed and unsuccessful. I do hope that’s not going to repeat itself.

You've now written eight books about old China, what keeps you going back to the past of the country?

There are so many good stories… And there are audiences for them.

While readers have definitely cooled on books about contemporary China (try selling your book on China today now!), my agents and publishers tell me audiences still find Chinese history fascinating. Old Shanghai, Peking, late nineteenth and early twentieth century Chinese history in all its complicated messiness and chaos is still appealing. I think people in Europe, Australia and North America are also aware that we are simply not taught Chinese history at school, so they have to seek it out.

I think there’s a lot of academics doing great work and books - and I thank them and read them (and try to acknowledge them where possible) - but few people are doing Chinese history for a wider audience. Sadly, it’s not an area Chinese historians themselves are really targeting today in China is shark-infested waters.

Though for me, an outsider, China is a great market. I sell a lot of books, my publishers are lovely, bookstores are super welcoming when I’m there, and I don’t get significantly censored. Chinese people want more Chinese history, it’s just trickier for them to write it in an appealing way at the moment.

How often have you visited China over the last ten years?

Until Covid I was spending time there around March and April - when Beijing, Shanghai and Hong Kong had literary festivals and I could combine research with events - and then again every October and November. I’ve managed to get back to Hong Kong and Macao again now and back into China, but not for long spells yet. But with Her Lotus Year coming out in China soon, the other books still doing well and, fingers-crossed, at some point a film of Midnight in Peking I think I’m destined to be going regularly again in 2025.

You have a great blog called China Rhyming, what’s it for?

When you do the amount of research I do - and I’m lucky that I sell enough books and get asked to write enough long-reads for magazines that I can research and write full time, you just amass so much information. So my blog has always been an aide mémoire (something that becomes more vital the older you get!), a place to note old photos, books, anecdotes to perhaps come back to later.

If you look at the long-reads I do fairly regularly for the South China Morning Post weekend magazine in Hong Kong you’ll see that many of those artists, writers or historical moments began as blog posts that I added to and came back to again and again and eventually thought ‘there’s a good piece in this.’ Instagram and Substack are also useful that way, but I still like to keep a blog going.

I don’t think anyone looks at China Rhyming regularly [Ed. they might do now!], but I get a lot of mail, and people who send me stuff, or answer questions I've asked online. People who happened to be researching their families or whatever and come across old China photos, documents, and news clippings and very generously send them to me. I like to help them out if I can.

In fact I wrote an entire book for Hong Kong University Press - The Old Shanghai A-Z - which deals with Shanghai old road names and those we use now because I got asked by so many people ‘what is Carter Road, or Bubbling Well Road, called now?’ or ‘Where was The Chocolate Shop or Bianci’s Pastries or Farren’s Nightclub?’ Now I just say, buy the book and hopefully it’s a good research tool for anyone diving into the geography and places of old Shanghai.

I understand that you're a big fan of John le Carré's The Honourable Schoolboy, much of which is set in Hong Kong. Would you be able to name your top 3 novels set in China?

Well, I think le Carré's THS is a masterpiece, his magnum opus and tells you so much about China after 1949 and into the mid-1970s, as well as Britain and America’s attitudes towards the PRC, that it should be on China Studies curriculums.

Three is tough! So I’ll avoid the ones I think everyone knows and always notes - Eileen Chang (Zhang Ailing’s) wartime-set spy novel Lust, Caution and JG Ballard’s loose novelisation of his time in Lunghwa internment camp, Empire of the Sun. I’m not going to opt for Kazuo Ishiguro’s When We Were Orphans - everyone recommends that to me and, while I know it has its fans, I’m not one of them.

Also, I’m going to assume everyone has read James Clavell’s Tai-Pan and Noble House - people today may not admit they are good, but they really are! The recent success of Clavell’s Shogun on TV and at the Emmys shows how good the source material is.

But here goes:

Man’s Fate (La Condition Humaine) - Andre Malraux (1933) - An amazing novel about the terrible events of 1927 in Shanghai and the massacres of the Left. Contrary to popular myth, Malraux did visit Shanghai, the book is pretty close to the events and those who read it at the time, such as Emily Hahn, praised it. (Also read his The Conquerors - Les Conquérants - all about the labour strikes and early Soviet involvement in 1920s Guangzhou).

Shanghai - Yokomitsu Riichi (1931) - An evocative representation of Shanghai by one of Japan’s leading experimental modernists who lived in early 1920s Shanghai. Riichi’s novel reveals the city as a melting pot of cultures, nationalities and ideas. One of the great omissions now in general thinking about old Shanghai, and China in general, is the impact of Sino-Japanese exchanges in literature and culture - Lu Xun, the Shanghai modernists… Japan is so important before WWII and now obscured because of politicking.

Midnight - Mao Dun (1933) - Mao Dun is right up there with Lu Xun, Lao She and Ba Jin and we really should have a modern and thorough new translation of this novel. Midnight is the best of the Shanghai-set novels by China’s leftwing realist writers of the 1930s, plainly laying out the harsh and often brutal capitalist face of the city while offering an intimate portrait of working-class life.

Now that your new book Her Lotus Year is almost out, have you already decided on your next big book writing project?

I have - and I’m already getting deep into it now - but my agent and publishers would take me out and shoot me if I talked about it just yet! Suffice to say - it’s China, it’s interwar, and it’s a big dramatic retelling of a true story with a lot of new information, perspectives and research.

How do you think China has shaped who you are now?

I haven’t done much else except China since university…. And that’s a while ago now. My best friends and close associates are all involved with China somehow. I do China for breakfast, lunch and dinner and I’m very privileged to be able to do that and love everyone that reads the articles, buys the books, and listens to the audiobooks.

I think China made me a better, more worldly person whose address book has people in every country who I've crossed paths with at some point in China. China gave me a network - when I go on long book tours around America, or the UK, festivals in Europe or Australia I am never short of people to have lunch, dinner or a pint with.

Living in London - where everyone passes through eventually - I’m always delighted when people from China days, or new people (readers, younger China folk, students, whoever) get in touch and want to meet up. It’s a great club to be in.

Paul French's account of Wallis Simpson's infamous year in China (1924/1925) - Her Lotus Year: China, The Roaring Twenties and the Making of Wallis Simpson (St Martin's Press in the US/Elliot & Thompson in the UK) will be published 14 November. Buy it here.

Enjoyed listening to Paul on a Le Carre podcast discussing THS recently. Thanks Simon. Interesting stuff.