That's Life

Meet Mark Kitto, former British army soldier turned China media mogul, who lost it all and reinvented himself as an author and actor - including a turn with David Beckham

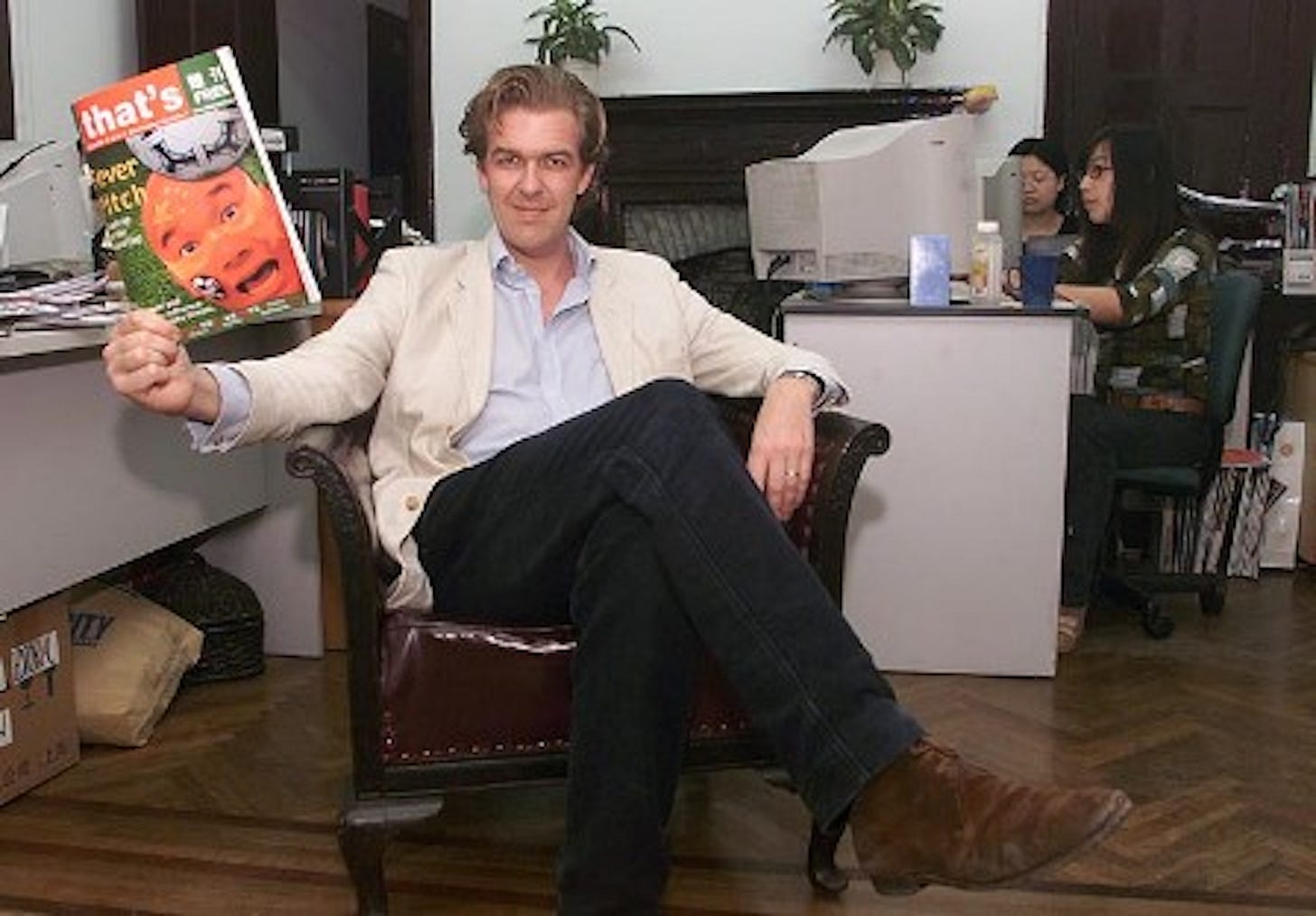

For old China Hands, the name Mark Kitto is synonymous with one thing - the early 2000s that's magazine debacle, where the hugely successful English-language print media business he had built up was stripped away from him practically overnight.

Disillusioned and despondent, Mark retreated up to Moganshan, a colonial-era hill station built in the mountains west of Shanghai full of deteriorating western-style homes. Here, amongst mock-Tudor residences and weed-filled swimming pools, he wrote his memoir that's China, a bare-all account that told his side of the story. Eventually relocating back to the UK, he later penned a sequel, China Cuckoo, that recalled his life spent in the century-old settlement founded by missionaries.

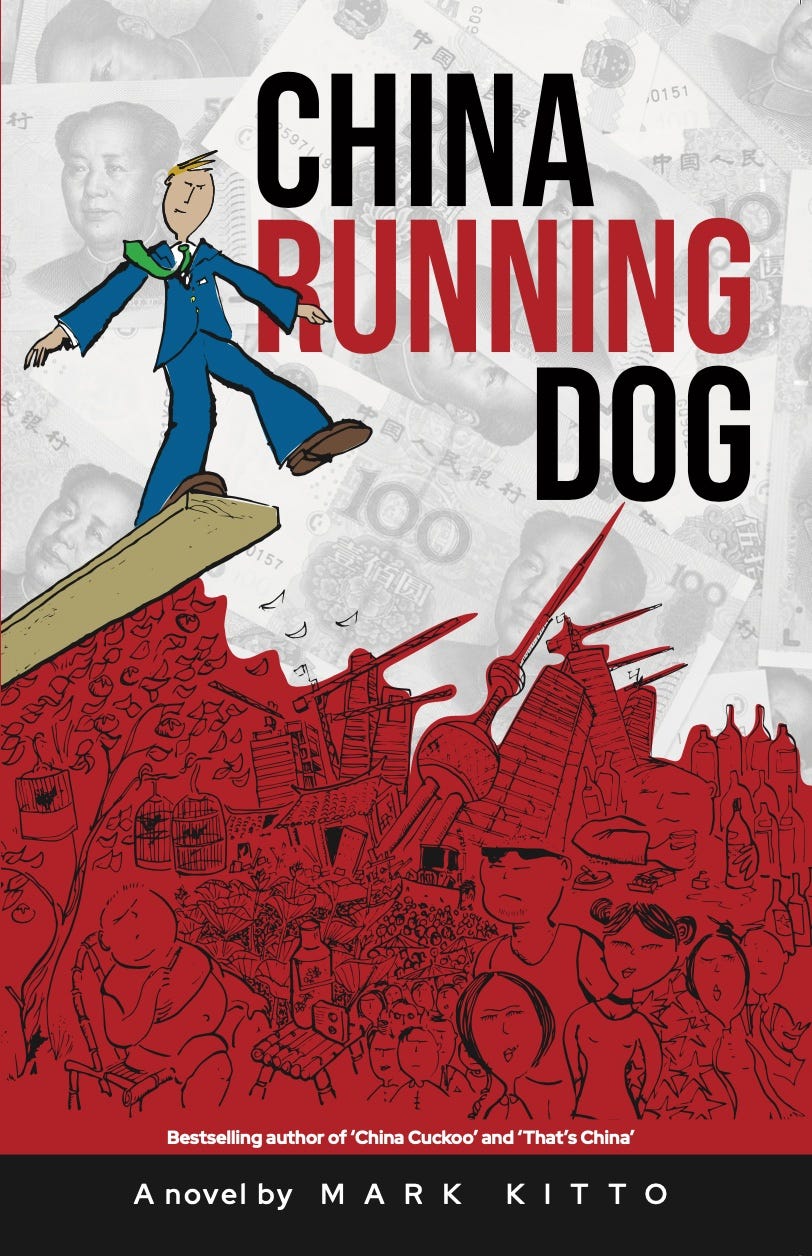

Mark has just released his third book, a novel called China Running Dog, a cautionary tale of doing the wrong things in the wrong places, set in Shanghai in the early 2000s. He’s also the writer, director and actor for his one-man show Chinese Boxing, which is set in 1912 and introduces the audience to Sir Claude MacDonald, a British official who survives the early 20th century Boxer Rebellion when Beijing's foreign embassies were besieged for 55 days in 1901. It's a balanced piece, that showcases the events from different points of view, and touches upon allegories to present day China.

Disclaimer: I worked for that's Shanghai in the mid-2000s as Food & Drink and then Deputy Editor, but was part of the group of editors and writers that came in after Mark's departure.

Hi Mark, I'm glad we've finally been able to arrange this interview. Let's start at the beginning. You were raised in north Wales - how would you describe your childhood?

In a word, happy. Qualification to that: single alcoholic mother and divorced disabled father, no siblings. So there were ‘pressures’. I escaped them first by exploring the Welsh mountains on my mother’s doorstep and then by going to China.

You then took a degree in Mandarin at SOAS, University of London. What led you to decide to study Chinese?

I was too young to realise the real reasons, as above. I used to say: languages at school, wonderful housemaster who encouraged me to read up about the Orient, and Deng Xiaoping announcing that he was ‘opening up China to the world’. Now I accept that underneath all that, I wanted to escape. I did fall in love with China.

You then served in the British Army as part of the Welsh Guards. What influenced you to join the armed forces? Was it a family tradition? And did you serve overseas at all?

Yes, family tradition combined with looking for adventure and not knowing what to do for a career. I was on a ‘short service commission’ and served four years in total. I went on exercises in Germany and Kenya and spent two years in Northern Ireland. The rest of the time I marched up and down outside Buckingham Palace in a bearskin.

The last thing I did while still in the army was take part in the first ever complete crossing of the Taklamakan Desert in Xinjiang. It was nominally a civilian expedition but about half of us were serving or recently ex-military.

Soon after leaving the service, you moved to China in 1995. Did you have any plans when you moved? What were your first impressions?

A London-based sponsor of that expedition, Wogen Metals, who had offices in China gave me a job and sent me out to Beijing then Guangzhou. First impression: ‘wow!’ compared to 1986 when I was at the Yuyan Xueyuan. All the cars, the street lights.

Let's touch on that's. How did the company start, and what do you remember about the first issue?

Kathleen Lau and I set the magazines up in late 1997, early ‘98. We each put in USD10,000 and worked every hour of the day. The first issue of ‘that’s’ was in Shanghai. We were stuck for a cover photo so I pulled a reject out of the bin and squashed it flat before we scanned it. Chris Gill took it. It was a pair of the artist Mi Qiu’s shoes. The cover words were something like ‘Stepping Forward’. Shelley Yip, our listings editor, filled up the events pages with countries from around the world’s national days. There was not so much going on.

For a while, it seems things went well. What would you consider the highlights of your time at the helm?

Crikey. Hard question. The whole thing was a highlight, yet also a terrifying rollercoaster. I loved it all, the highs and lows, the fights (with the government bureaus) and the fun (with everyone else). More specific: sending staff to intern with Time Out in London, giving the chief of the Cultural Investigation Bureau an apoplectic fit, launching that’s Beijing (by which time I knew what I was doing and had a brilliant team there).

In 2004 you lost the business, yet you decided to stay and fight through the courts. Without dwelling too much on it, what made you appeal, despite knowing the likely outcome?

The 10,000 had become a turnover of 4 million a year. I had bought out Kathleen. I had to fight. I could not just walk away. And I won the appeal, for about five minutes. Then the decision was cancelled by you know who.

Then, instead of leaving China, you headed up to the hills of Moganshan. Were you not just tempted to pack it all in and go back to the UK?

Yes, and no. I probably should have done. But I had just invested most of my savings in renovating our house, which had been derelict, on the mountain, and paid ten years rent in advance. I loved the place.

What was it like when you first arrived? I understand you were the first foreigner to live in Moganshan in 60 years?

I hate that ‘first foreigner’ BS but I’m afraid I was the first one to go back and actually ‘live’ there. But I must point out, back in the day none of the foreigners really lived there in the first place. It was summer homes. Hang on, one of them did live there permanently, the resort manager, and he was murdered. What was it like? Untouched, a semi-ruined heaven inhabited by locals who all grew up with foreigners. There was no ‘Lao wai!’, just shrugs and, ‘Oh look, a foreigner has come back.’

Moganshan has now become a major tourist center. Do you regret not staying and building a hospitality empire, much like you'd done for English-language media with that's?

I regret very much that I could not buy a property there. No one can. Moganshan put me back together after losing my media business, and the locals were friends. And it was a wonderful place for the children to grow up. I am deeply fond of it. But the main village where I lived, on the top, above Naked Stables, is fated by local politics never to be a place people can call a settled home. Even the locals get pushed around.

In 2013 you finally did move back to the UK, which you say was for your children's education. In what sense do you mean? Obviously there are many international schools to choose from now in Shanghai and other Chinese cities.

I wasn’t keen on international schools for my children, though I must be grateful for their advertising budgets. I wanted my children to have a local China life for half their education, and a local English one for the other half. I think it has worked out well. Right now Isabel is studying in Tokyo and Tristan is in Zambia. That’s international.

How did you find the adjustment to life in the UK after years in China? Twelve years on, do you feel you've fitted back in?

It was of course a struggle to begin with. Everything is so slow and established. You have to obey the rules. I have adjusted now, and I do love being home, especially London.

I understand you became a professional actor in 2018. What led to the career change? Was it something you'd always been interested in? What type of amateur dramatics and performances were you involved in while in China?

I did not know what else I could do in the UK. I started a small media business but while it worked (in fact it had great potential) and could have expanded, it would have taken every working hour again and I have done that. I am also older and slower.

I’ve always been interested in drama. I put on a play at the Yuyan Xueyuan, reputedly the ‘first’ foreign student play held there. I was in Cabaret in Beijing in 1996. That was a wonderful production. And I performed professionally with the Shanghai People’s Arts Theatre, briefly.

On your acting CV you mention you played a Chinese-speaking London cabbie for a David Beckham promotion. How was that experience?

You found the link. Are you going to put it on this post? [Yes, view it here!] How much can I pay you not to? Seriously, Beckham is charming so long as you talk about football. I got him to reminisce about his trip to Shanghai in the late ‘90s too. We put Manchester United on the cover of that’s Shanghai with the words: ‘Man Who?’

What do you think are the key traits that make for a successful actor? And how have you found auditions?

Where to start? Simple answer: Bloody minded perseverance, a skin like a rhino for all the rejections, a positive attitude and some talent, generally hard earned through practice. I love auditions. I want more.

In 2020, with the world withdrawing in shock from Covid, you wrote your one-man show Chinese Boxing. How did you find the process, and how difficult is it to write a play where you are director, producer, set manager and actor?

Right now I am writing these answers in Singapore where I am about to do the show and it is incredibly difficult. One of my vital props is either in lost luggage or still in Heathrow. I got the performance permit only a few days ago. I have barely any time to promote sales (plug! plug!)

The research took a while, the writing no time at all. The characters quite literally walked onto the page. But then the hard work, with a wonderful dramaturg, Marlie Haco in London, was, as she put it to: ‘take a good story and turn it into a drama.’

What has been the audience response? Do you find the show attracts old China Hands?

Audiences love it, once they have got their heads round it. It is different, possibly even unique. And yes, China Hands seem to enjoy it. I’ve had a former Swire taipan, the Consul General from Shanghai and Edmund Backhouse’s granddaughter among others. They all approve. I like to lighten up the post show Q&A with amusing anecdotes. It’s become a bit of a stand-up routine with a few serious bits.

You're taking the show overseas to Singapore in May. How do you think it will be received?

I think it will go down well with the international community. It’s been really tricky getting Chinese audiences in the UK to come but once they do, they have been super appreciative. The play is after all about their point of view of the Boxer Uprising, which, as I am sure you know, is called ‘The Eight Nation Army’ invasion in China. I hope there will be Chinese audiences in Singapore.

You now have a new book, your first novel, China Running Dog. In short, what is it about, and what do you hope readers take away from it?

It’s about two Brits in millennial Shanghai. One’s bad, or let’s say a bit ropey, who turns out good, the other starts out good and goes horribly bad. Pushing and pulling them are a cast of characters, mostly Chinese, again some good some bad, and some surprises. It’s had some nice reviews so far. Adam Williams, another China novelist, describes it as ‘a hilarious, racy, cautionary tale. A must read for anybody who wishes to see how a totalitarian society works’. I like that.

At some point, would you consider working on a project not about China, or - having spent decades there and speaking the language - it is too ingrained into who you are?

Of course I would consider it, and I do think about it and have ideas. But I still have China stories I’d like to write, about Xinjiang for instance, and I have an idea for a play based on an arts delegation that went to China from Britain in 1954. I’d also like to try to expand my one-man play formula where, as in ‘Chinese Boxing’, I tell a story from three conflicting yet complimentary viewpoints. There are other conflicts or historical episodes that I could apply it to.

It's been 20 years since that's - how do you now view what happened in Shanghai in the 2000s? Have the years given you a different perspective?

That’s an enormous question. Best and obvious answer: read ‘China Running Dog’. It’s all there. Available on Amazon and direct from the publisher, Plum Rain Press in Taiwan, by the way. I think I and my contemporaries were very lucky to live in Shanghai, and China, at a really exciting, positive time.

Looking forwards - what does the future hold for Mark Kitto?

More acting, more writing. I just got to the last two in the audition process for a major West End stage production. A small role but great play. I have to keep trying. And I have a plan for a sequel, and then another to make a trilogy for China Running Dog. I just wrote the first two pages on the plane to Singapore this morning in fact. There’s a major ‘arc’ I want to complete. And I got remarried almost a year ago, so there’s lots of building a life together going on, which is wonderful.

Interesting. You always find some gems…