Of Gods and Men

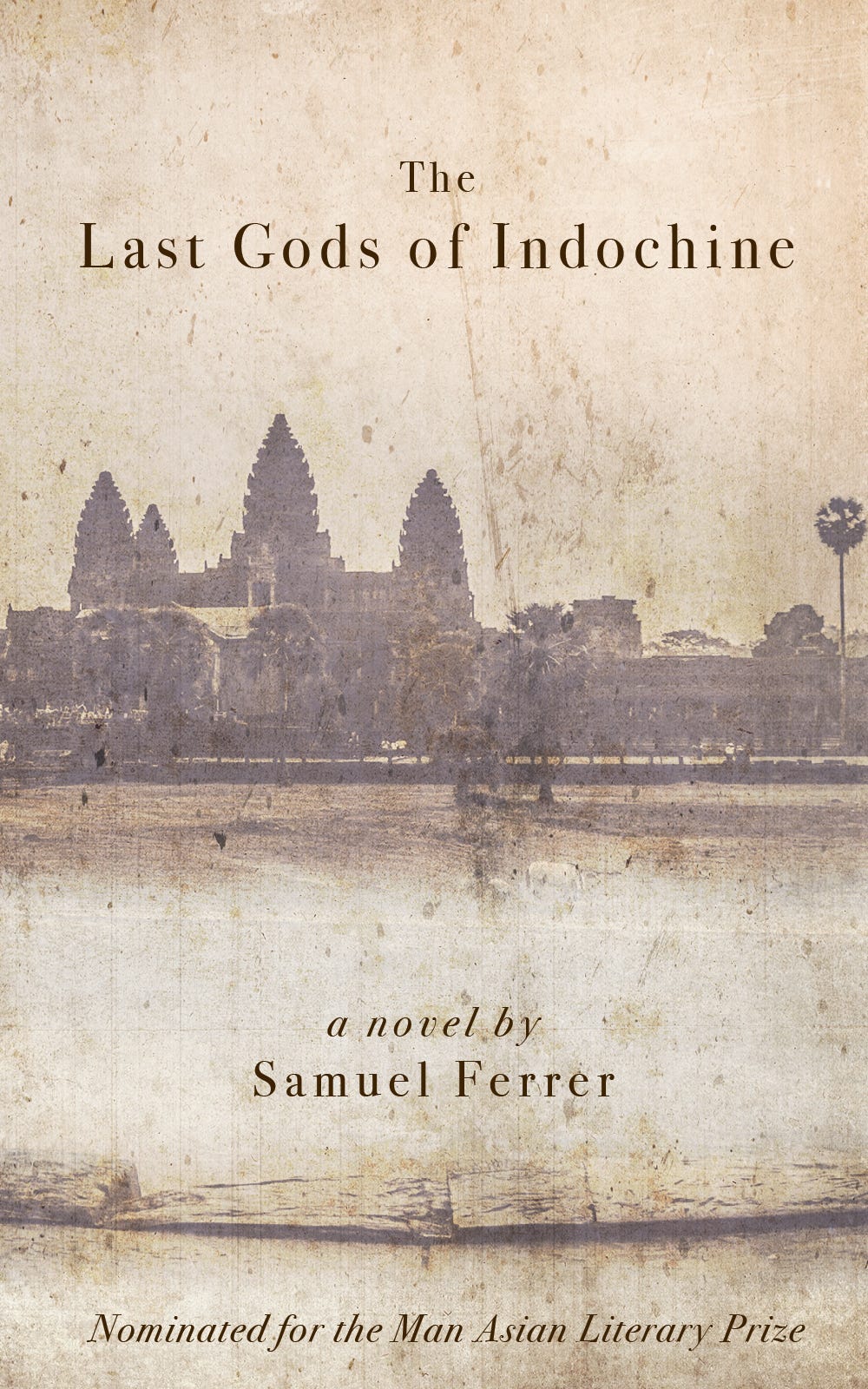

For author Sam Ferrer, writing his first novel The Last Gods of Indochine was not only a voyage into the distant past of Angkor Wat, it was also a journey of self-discovery

Sam Ferrer is a man of many talents. A talented musician who is a double bassist for the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra and band leader for acid jazz group Shaolin Fez, he is also the author of The Last Gods of Indochine, a gripping work of historical fiction long-listed for the Man Asian Literary Prize that intertwines the story of a French explorer and Cambodian orphan to examine a curse that befalls Angkor Wat, the famed heart of the Khmer empire. I first met Sam many years ago when I was Books Editor for Time Out Hong Kong, but following my move to Phnom Penh, and subsequent first ever visit to Angkor, we re-established touch and he sent me a copy of his book by surface mail. Five months later via a very slow boat from China, the book finally arrived (with a second copy for the Cambodian Book Collector). Enthralled by the tale, I asked Sam what led him to such an original story, what's taken so long to write the second one, and if being able to make music makes it easier to pen words.

You're an acid jazz musician based in Hong Kong, what led you to ancient Angkor?

When I moved to Hong Kong from New York City, there was no destination higher on my travel agenda than Angkor Wat. It had already captured my imagination as one of the most exotic and remote sites in the world. I had only been living in the east for a few months when I used my first vacation opportunity to pack my bags for Cambodia.

When did you first visit Angkor Wat, and where have you travelled in Indochina?

That was in 2002, and I returned about four years later purely for the sake of research for the novel. As for the rest of Indochina, I’ve been to Vietnam three times and Laos once. My first time to Vietnam was back in 1998 while on tour professionally, which marked the first time an American ensemble had performed in the country since the war. There were wartime generals in attendance of our concert at the Hanoi Opera House. Of course, the country was nothing like it is now; it took a bumpy 5-hour drive (one way) on a dirt road to get to Halong Bay, which had no tourism to speak of, not even a place to spend the night. No exaggeration – we only crossed paths with two other boats in the bay throughout an afternoon there, a far cry from how it is now.

I made a couple more trips back to Vietnam as writing retreats. I also got some work done in Laos, where I saw much of the country over three weeks, including staying in the electric-less huts of the remote Four Thousand Islands way down the Mekong for US$1.50 per night. Fortunately, in the daytime I could charge my computer at a hut ‘restaurant’, where I’d make an order from a girl who would promptly disappear on her bicycle and return later with the necessary ingredients to cook my meal up. I met some really interesting characters down there. This was just before the giant tsunami that devastated Thailand and Indonesia and some of the travelers with whom I’d spent time with in Laos, on their way south, were killed shortly thereafter, as I later found out.

I've seen a photo of you at Henri Mouhot's gravesite, how was that experience?

That was just outside of the wonderful town of Luang Prabang in Laos. In fact, it’s only a 20-minute bicycle ride and then you take a short trail to the site. Hardly any tourists go there, certainly not the locals, because it doesn’t really mean anything to them, but of course it meant a lot to me. It was rather profound, his life and journals being the inception for my story for which I would spend over a decade of my life.

Although a novel, the book features historical people, how did you research them?

As for Henri Mouhot, he left an extensive journal of his travels to Angkor, including exceptional drawings. He was an artist in addition to being a naturalist. That was published not long after he died there in 1861 and became quite popular in France, when Europe was still ‘discovering’ this part of the world. He even went so far as to describe Angkor Wat as more magnificent than the architectural gems of the West, which was considered sacrilegious to the Western ethnocentric sentiments of the time. Posthumously though, he became one of the most famed explorers of that generation.

As for the history of the region, early resident scholars George Cœdès and Francis Garnier wrote some books that were an invaluable resource to me, English translations of which can still be ordered through a small publisher in Thailand. I learned about Henri Marchal and Victor Goloubew through the internet. They worked for L'École Française d'Extrême-Orient (the French School of the Far East, which was dedicated to the study of Asian societies), after the turn of the century and I had a lot of fun with those characters, whose historicity I explain in the afterword. In the ancient story I inserted the Chinese emissary, Zhou Daguan, whose 13th Century musings on the Khmer Kingdom were critical for my depiction of their culture during that era.

I also read a fair amount of Hindu literature, some myths which are referenced in certain scenes in the novel, as well as journals by World War I nurses for Jacquie’s backstory. On my second trip to Siem Reap, I was able to secure an interview with the director of the EFEO, which I didn’t even think existed anymore. I only found out after coming up empty handed in a library, when the librarian finally asked me, “If you are looking for information about the EFEO, why don’t you just go and visit their estate?”

So, I hopped onto the backseat of this kid’s motor-scooter that I had hired for the day and we drove through the rain to their offices. There, I was able set up an appointment to see the director the next day. Upon returning and meeting him, I began to probe with questions about where the structures that once housed EFEO would have been back in the day, and if there were any images I might be able to see. He surprised me no end when he looked at me with a kind of French exasperation and fluster, and then exclaimed: “It was right here – these are the same buildings. You’re sitting in it!”

You could have used the modern day as a setting, what drew you to the 1920s?

I’ve never been asked that question before. It’s a good one. Without a doubt, it would have made writing the novel infinitely easier. But I knew I wanted the setting to be as rich and fascinating as possible. In fact, I was inspired to write my own novel after reading Daniel Mason’s The Piano Tuner, a colonial story set in Myanmar. Setting went a long way in making that novel work, and I felt that, at a minimum, it was something I could achieve with enough diligence. For the French, there was nothing more exotic than their colonies in the east, with Angkor Wat being the crown jewel of the empire.

I wanted to tap into that culture, a society that would do something as extravagant as rebuilding the top level of Angkor Wat to scale for the Colonial Exposition in Marseille in 1922. Reading about that alone did a lot to stir my creative juices. Yes, I thought: I could create a fictitious granddaughter of Mouhot who would be commissioned by the Colonial Exposition to follow his footsteps and visit the EFEO archaeological projects.

You don't over-romanticize the colonials, is that something you were conscious of?

Yes, and it’s very interesting you would say that. I was acutely aware I was stepping into sensitive territory by writing a novel set in the colonial era; political correctness has made such an endeavor fraught with landmines. Some Western reviewers have made the exact same observation as you, presumably because I didn’t shy away from portraying the assumptions and exploitations of the day, odious as they were. And it should be evident in the novel that the tensions with the colonial powers would not be endured for much longer. Yet, a couple of critics – Easterners this time – came down on aspects of it nonetheless, feeling I had come up short from a cultural standpoint.

One said that – in spite of my efforts – the very fact that the regional culture was depicted as mystical while the colonialists were scientific revealed my prejudiced, Western hand. The other questioned why I had to ‘focus’ on barbarism in the ancient story, referring specifically to a human sacrifice (as portrayed in the Hindu tradition). Both criticisms left me at a loss: it would have been inaccurate to portray remote, agrarian communities of developing countries as living anything other than far behind their colonial overlords or to deny them their closely held religious beliefs. Even on my first trip, most of the community in villages around Siem Reap were still living in huts.

I suppose I could have made the staff of EFEO devout Catholics and brought some attention to their own mythical beliefs, but to my knowledge, they weren’t. As for the barbarism and human sacrifice in the ancient story: at Angkor Wat we can still explore with our own hands slabs of rock made explicitly for human sacrifice ceremonies, and sacred Hindu texts dictate what to recite when performing the rite. I put two and two together and included the text in the novel, and I suspect that critic didn’t appreciate that particular ghost from Cambodian religious history being pulled out of the closet.

But to me, this is all fascinating not because it is their history and I’m pointing a finger at anyone, but rather because I see it as our history, collectively. One could say, why don’t you just write about the superstitions or barbarism of your own culture? But as the character in the novel, Victor, answers when asked why he went all the way to India to study other religions, that inquiry doesn’t interest me nearly as much because it has already been done ad nauseum. The Inquisition, the Crusades, the Salem Witch Trials…. how can I bring anything new to any of those? As yet, nothing has come to me. Maybe someday something will. But during my earliest draft of The Last Gods, about 15 years ago, there was very, very little, Western written historical fiction set in Cambodia, and so I saw it as largely unexplored terrain for us. And I wanted to go about it as honestly as I could, no matter where that took me. So, the opinion that I should censor myself when depicting the East is not a viewpoint to which I’m willing to bend, because it is alleged I have no right. This is our world, this is our history.

It's an ambitious tale for your first novel, was it just a story that needed to be told?

I would never recommend to anyone to do what I did for a first novel. Honestly, I think most people would’ve probably just given up. Historical fiction requires the most research and a parallel story set in a completely different era doubles that research. I am not a historian, an archaeologist, or a scholar on Eastern religions for that matter. And for some reason I chose a female protagonist. Lastly, I was still learning how to write. But having said all that, I never once doubted my premise and concept for the novel, so it had to be done. May thine own creative inspirations be closer to home.

I understand you're working on a new novel set in Israel, tell us more about that.

It’s another story that has to be told, a premise that came to me over a decade ago while writing The Last Gods and has haunted me ever since. Fortunately, it is modern and that saves me a couple of years of work. I won’t give much away, but it explores eschatology, or end-of-times beliefs, of which there is a multitude that all lead to a geographical point in the Holy Land, a tinderbox of beliefs if there ever was one. It will explore how firmly held faiths can collide with one another and how consequential that can be to society as a whole. It’s taken me a long time to get to it because after completing The Last Gods I wrote and produced two albums for my band, Shaolin Fez, each of which took the same amount of time it would have taken to write a novel.

When writing a book, what parallels do you find with composing new music?

The creative process is not the same at all. With music, I’m usually struck by lightning with a melody at random moments, I sing it into my phone’s memory, and then I have to sit down and arrange it for Shaolin Fez, which is the intensive labor part, especially as we are a symphonic jazz-rock ensemble that uses up to 14 players live, and even more when in the studios. On the other hand, writing fiction starts more with the intensive labor and then figuring things out like an elaborate, cerebral puzzle.

If I make you choose, what are your all-time favorite books and writers, and why?

If I had to choose one, it would be Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1972. He is arguably my favorite writer and most people have never heard of him. The writing is gorgeous, the metaphors anchor you to the characters, the relationships thoroughly relatable and engaging. Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things is a book whose full force didn’t hit me until a couple of readings later; the first time I read it I wasn’t yet a writer myself and I didn’t get just how brilliant of a job she did with it. The Perfect Man by Naeem Murr, another author not known nearly well enough, was a masterclass in characterization, not to mention prose. Cold Mountain by Charles Frazier is a stunningly beautiful book. Those four novels I likely studied more than any others while writing The Last Gods. I’m also drawn to the works of Cormac McCarthy and Jonathan Franzen. Curiously, this is an American dominated list.

For anyone thinking of writing their first book, what advice would you give them?

Feedback, feedback, feedback. Seek it out anywhere and everywhere, especially from fellow writers, and do not fold under the criticism. Instead, embrace it. Learn from it, and then ‘fail better’ with each revision. Someone once said, ‘You cannot edit a blank page.’ So don’t worry if it is crap or not. It probably is – but instead see it as the clay you have set out to sculpt. The key is to start with a premise you know is so special you will see it all the way through, because no one else is going to write that story. I don’t think of myself as a great writer, I think of myself as a fastidious and indefatigable editor. No exaggeration, I probably made over a hundred revisions of The Last Gods of Indochine, but having now paid my dues, the next one may only take a couple of dozen.

Sam Ferrer is obviously intelligent and creative and I imagine that he is gifted with (or has developed) strong self-belief and persistence. A necessary balance of gifts, talents and attitudes that bring his ideas into reality. I very much enjoyed reading this article, Simon. I also think that Sam’s advice to people who want to write their first novel is good advice for people who are wanting to start any project.