Join the Club

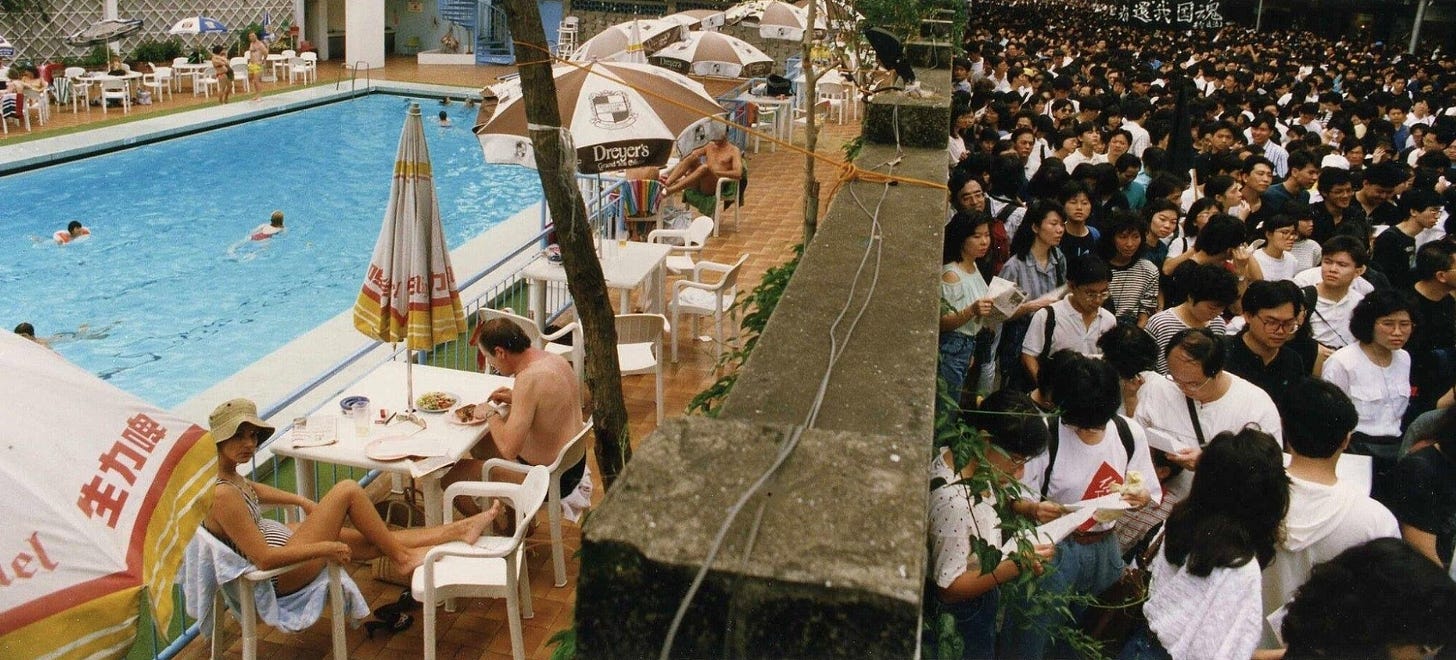

Snapping a moment in time, journalist Steven Knipp's remarkable shot of protests in colonial Hong Kong captured the stark divide between expatriate and local society

After being donated to the Foreign Correspondents Club, where it hung on a wall in the Hong Kong institution’s bar, the photo was recently back in the news when Knipp called for its return, in protest against what he said was its failure to defend press freedom in the city. I got in touch with Knipp to find out more about his famous shot.

Thinking back, what are your first memories of Hong Kong?

I first came to Hong Kong in the late-1970s, as a young tourist, and was overwhelmed by how exciting and exotic everything was. And how physically beautiful. I had a window seat on the plane. In those days, it was an exhaustingly long flight from New York, stopping for fuel in Alaska and Okinawa, before final approach into the famous old Kai Tak Airport.

As the pilot dropped lower, the South China Sea finally came into view. It was late afternoon and I remember it being a shimmering silver, pieced by a gaggle of high green islands.

A few seconds later, the pilot suddenly veered to the left and dropped the nose steeply. The plane was a DC-10, but the captain was flying it like it was a fighter plane. This was our final approach into Kai Tak – a long concrete finger pointing into Victoria Harbour.

All around us were thousands of towering white skyscrapers and jagged mountains –including Lion’s Rock. At this point I thought the pilot would throttle back his engines as happens most everywhere else in the world. But instead he powered up to what seemed like 100 percent and the engines started screaming.

Just outside my window and seeming just a few seconds from crashing into us were old eight-storey residential apartments, the flat roofs festooned with colorful flapping laundry. I could literally see people staring out their windows – at me.

Suddenly we shot over an expressway and seemed that our landing gear nearly beheaded a double-decker bus. I saw a barbed wire fence flash by, then we were racing down a runway, with the harbour on both sides. The pilot must have been standing on his brakes, because just before we reached the runway’s end and tipped over onto the sea, we stopped. Passengers were suddenly clapping like it was all a performance!

A minute later, having turned around and taxied to the terminal gate, the whirring sound of those amazing engines stopped. A strikingly attractive stewardess (no one called them flight attendants in those days) pulled open the passenger door. When I arrived at the plane’s exit and stuck my face out, a shocking wave of heat and humidity hit me like a punch. And this, in December!

I remember thinking: “I’m gonna need a longer holiday!”

What do you remember about the day you took the photo?

The massive (it was reported that nearly a million people showed up, but less than half could get into the racetrack) rally was in support of the protesting students in Beijing as there were deep fears of what the Chinese army would do to them if they kept demanding democracy. And a few days later, those deep fears became a reality with the massacre.

The planned rally at the famous Happy Valley racetrack had been widely reported on TV, on radio and in various newspapers the day before. So I and my then girlfriend – now wife – knew that we wanted to go. We took a cab, but halfway there, massive crowds, all dressed in white, the color of mourning in local culture – started appearing on the sidewalks and tumbling into clogged streets. We jumped out, but when I went to pay the driver, he absolutely refused to accept the money. I kept insisting, but he refused.

I was deeply touched because, as anywhere, Hong Kong cabbies are not known for being sentimental. But this driver seemed gratified that a gweilo (foreigner) would make the effort to attend this outdoor event about endangered Chinese students in distant Beijing.

You're a journalist not a photographer, so how did you end up with the camera that day?

I’ve been in love with photography since I was 10 and received a camera as a gift. Gradually I came to the habit of almost always carrying a camera, about 90 percent of the time. I find that when you have a camera with you, your senses really become sharper than normal – you notice patterns of light and colour and shadows more. You’re more likely to spot strange or interesting people out of the corner of your eye.

Years later, when I got to meet and interview famous photographers, they all told me the same thing: You could be the world’s most talented and skilled shooter – but if you see some amazing situation and don’t have a camera on you, none of that background will matter.

How did you end up in that location, and why did you climb the wall?

Some 20 minutes after leaving the taxi, we had walked from the shopping district of Causeway Bay to the rather more posh and leafy residential neighborhood of Happy Valley. We entered Wong Nei Chung Road – which the police had blocked off to all vehicular traffic. This street would bring us to the entrance of the historic race track. But just before we arrived at the track gate, I spotted a seven-foot wall which ran parallel to Wong Nei Chung Road. Behind which was the Hong Kong Football Club.

By this point, the protesters were 25 abreast in the road, packed tightly, all moving forward slowly, but patiently. I had purposely packed a wide-angle lens to capture the scale of the crowds. But standing in the midst of all these people, there was no way I could get the type of shots I wanted. So the instant I saw that wall, I know I needed to get to the top, so I could look back down at the crowds to photograph how massive they were.

Somehow I managed to scale the wall. And as soon as I did, I was amazed to see that on the other side was an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Plus a pile of expats sitting around enjoying their weekend – as if there weren’t hundreds of thousands of protesters just beyond their wall. I was gobsmacked by the jolting juxtaposition. The caring and the un-caring. The well-wined and the great unwashed.

What was the response from the club-side, that expat lady with the hat looks seriously annoyed.

As soon as I pulled my camera out, I started snapping the shutter, trying to place the wall at the centre of each photo. Originally, all the tables by the pool were full with people. But very quickly the smart ones skulked off – aware of how they must have looked in my view frame. But the lady in the foreground held her ground, staring at me with daggers for eyes. Meanwhile, note how her hapless husband steadfastly kept his focus on his tuna fish sandwich.

I wasn’t sure how much time I had, as I expected security guards to show up at any moment telling me to get off the wall. But they never did. After about two minutes, several other photographers climbed up on the wall next to me. But, much to my surprise they only wanted to shoot the massive crowds on Wong Nei Chung Road. None seemed to notice the historic moment in time that I had.

What was the reaction like when the image was published?

The next day I took the film rolls for development, and that same afternoon I selected one transparency to make an 8 and 10 print. The next day I took the print up to the FCC at lunchtime, where I knew there was always one particular table at which all the top professional photographers lunched.

One of these was a friend of mine, a lovely Dutch photographer named Hugh Van Es who, many years earlier had taken one of the most famous photos of the Vietnam War. The image of the American helicopter taking people off a rooftop in Saigon, to escape the rapidly approaching North Vietnamese Army.

As soon as I showed Hugh my photo he became very excited, even agitated, saying it was an historic image! Completely unique. Of course I was thrilled to hear this. Not long after that the FCC asked if they could display the photo on the Club walls and of course I was exhilarated again.

And from that day on, for many years, whenever I entered the Club for a lunch or drinks on a Friday night, Hugh and the whole ‘photographers’ table’ would tease me mercilessly. They’d shout out, above the bar noises: “Oh, look! Here comes the world’s greatest photographer!” knowing full well that I was a reporter and writer, not a professional shooter.

Over the years, that photo has been printed in various newspapers and magazines across Asia, the US and UK, and in at least one book. I donated all the fees to the FCC’s staff Christmas parties.

Why did you decide to ask for the photo to be returned?

It was a hard decision to ask for this image to be returned. Because of course I was honoured to have it on display at the Foreign Correspondents Club. But recent events convinced me that that the Club was no longer the respected institution it once was. And statements made by the current Board made it clear that the Club no longer intends to actively defend press freedom in Hong Kong. So, as a journalist of more than 30 years, what choice did I have. Hopefully the Club will continue as a great bar and restaurant. But I did not want this photo – of thousands of people peacefully protesting – to be used as a kind of prop in a Potemkin press club.

Epilogue

There are some photos that stick in your mind forever, and for some reason many of mine have been combative. There's the famous 'Tank Man' picture in Beijing 1989, Hubert Van Es 'Fall of Saigon' photo, and one I more recently discovered, Roland Neveu's 'Photo of Life and Death' (my title). However, the one that I recall the most comes from my own childhood, and combines two memories I will always live with.

Growing up in colonial Hong Kong, sporting clubs were a big part of the expatriate lifestyle (to be fair, they still are now - also see Singapore). Over the years my parents were variously members of the Football Club, Cricket Club, Jockey Club, China Fleet Club, Mariner's Club, and the 50 Cent Club (wait, I think that last one is actually a song). However, it was the first of these institutions that was the most formative.

During one of the earliest editions of the famed Rugby Sevens - which were held at the Football Club's own arena before moving to the larger surrounds of the Hong Kong Stadium when the tournament grew - as a baby I was left beneath the stands (my parents had likely had a few San Miguels too many). Later, I learned how to swim in the club pool, including treading water in my pyjamas for a badge of some sort. We also used to borrow videos (that's VCRs) from the store under the stands, and at some point my parents edited the Club magazine, and dad headed up the Football Section.

On weekends, we'd often be found hanging around the pool, eating club sandwiches and hot dogs, sipping on Gunners (a truly refreshing blend of ginger beer, ginger ale and Angostura bitters), all of which was signed for on the chit (you were billed at the end of the month). I even carried around the Club sports bag for years, using it for weekend school football matches on the pitches in nearby Happy Valley. It was such an intrinsic part of my childhood, and a place I honestly still miss now, though the move to a shiny new clubhouse in 1995 ironically saw it lose much of its luster to me.

All these memories came flooding back to me recently when I read a news story about a journalist called Steven Knipp who was withdrawing a picture he had donated to the Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents' Club (FCC), as a protest for it failing to stand up for press freedom. The photo, for me, deserves to stand alongside the pantheon of great images, summing up in one image - as the best pictures do - a moment in time.

Simply, the June 1989 photo shows colonial-era expats sitting by the Football Club pool while their kids splash around, while on the other side of a six foot high wall stand massed ranks of Hong Kong Chinese, many dressed in white, the traditional colour of mourning in Chinese culture, as they march past in solidarity with those soon to be stricken down in Tiananmen Square. It's at once an acknowledgement of colonial indifference, yet also it signifies the temporary nature of local British rule.

The Joint Declaration handing Hong Kong back to China had been signed some four years earlier, and in eight more some 150 years of British rule would come to an end. Yet, in this image, for one side it’s a plate of Singapore noodles, for the other, fear and anger at what the rapidly approaching future may hold. For a long time I imagined I might have been one of the kids in that photo, swimming in the pool, but then, just a few years ago, I discovered my dad had actually taken me out on that protest march.

It must have been unusual, a British colonial civil servant taking his 10 year-old son to see the nascent beginnings of the creation of a Hongkonger identity, yet it has imbued me with the ability to call the city home, no matter what side of the fence you sit on.

An amazing photograph that really captures a moment in history, such contrasts and a very interesting interview too !