Ich Bin Ein Hongkonger

After years of struggling with my identity, I ended up defining myself as Hong Kong British, but can an expat kid with a German surname ever really be a Hongkonger?

Growing up as a white expat kid in Hong Kong, I was extremely privileged. Of course, I didn’t know it at the time - a life of sports club memberships, two cars, and a 2,287 square foot apartment seemed perfectly normal to me. My family had arrived in the British territory in early 1980, my father taking a job with the Hong Kong government as a land surveyor, a three year contract that ended up becoming a quarter century.

As the story goes, he’d answered an advert in the magazine of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors calling for colonial civil servants, and my parents had moved with me in tow as a baby. It was only meant to be a temporary jolly, a few years in the tropics before heading back to the UK and resuming a surveying career in London, but - as these things so often go - the lifestyle on offer was too attractive to give up. Not to say that life was entirely easy in those early days - we had a VW Beetle car with no air-con, and my mum recalls once running out of gas in the Cross-Harbor Tunnel.

Those early months were spent living in the old Lee Gardens Hotel in Causeway Bay, before we moved to the nearby Leighton Hill Government Quarters (built in 1948, they once had commanding views of the harbor, as this photo by WJC Kitto shows). The government quarters were a special perk of being a colonial civil servant, with a variety of apartments, bungalows and houses dotted around the territory that were allocated to government staff via a points system that depended on seniority, i.e. the more you were promoted, the better your digs. Most of them are now gone, sold to developers who put ‘the’ in front of the name to fancy them up, such as The Leighton Hill, The Belcher’s, and The Caldecott, though a few, like Mount Butler, still stand.

Following the colonial template, my parents joined the local sports clubs, a list that eventually extended to at least six that I can recall, including the Hong Kong Football Club, where at one point my dad headed the Football Section, and both of my parents were editors of the monthly Club magazine (a subconscious inspiration for my later career as a magazine editor). It is also famous as the original home of the Rugby Sevens, before those annual festivities relocated to the Hong Kong Stadium. For education I was sent to the English Schools Foundation, a group of international schools that was essentially founded to provide schooling for the expat children of government staff and police officers (though now is far more diverse), attending first Quarry Bay, and then South Island, from where I eventually graduated. Along the way, friends were made and lost, as new students arrived and - in many cases - left again.

On the home front we had a live-in maid who took care of almost everything in the household, my dad regularly moved around the city’s far-flung district offices, while my mum worked full-time as a teacher at the very British sounding King George V School. If we weren’t at a club, weekends were spent hiking in the country parks, going on boat trips to offshore islands and beaches, and hanging out with other expat families - looking back, it seems fairly idyllic. However, at some point during growing up, two major events had happened that I didn’t realize the significance of at the time.

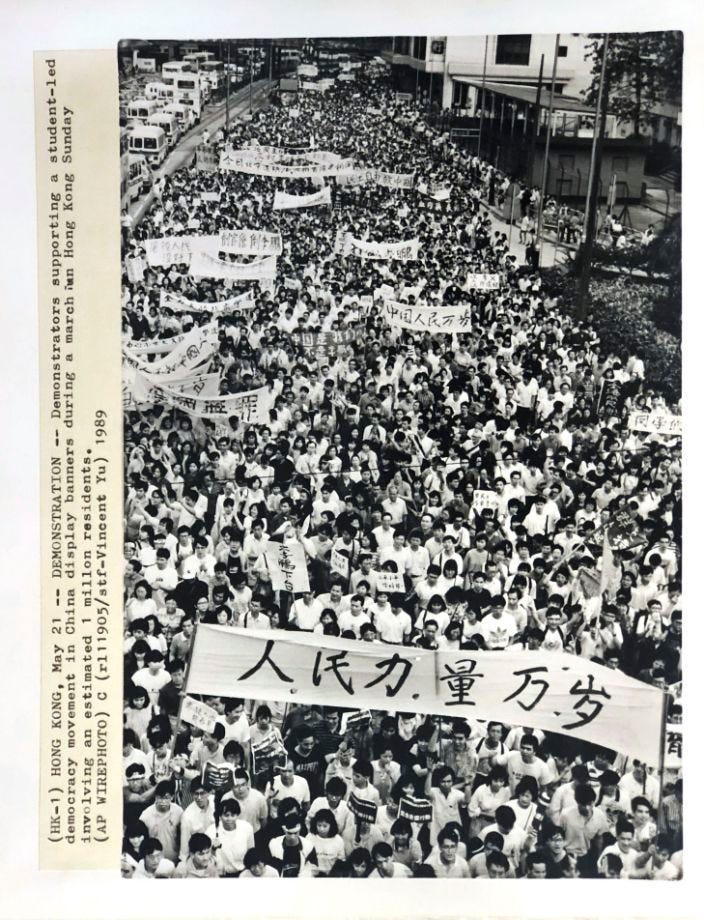

In 1984, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher signed the Joint Declaration that promised to hand all of Hong Kong back to China in 1997. She had fallen down the steps of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing a few years earlier in front of Mao-suited cadres, surely an ominous sign. Then, five years later, came the Tiananmen Square massacre, and the PLA-led crackdown that came to be synonymous with ‘Tank Man’. Hong Kong erupted in protest, and my father put me on his shoulders to witness firsthand the million person march. Sadly, I don’t remember much about that day, but it did begin the first stirrings of a sense that this city meant something to me.

Hong Kong (much like me) has always had an identity problem. Originally a base for fishermen and pirates, Britain forced the Chinese to cede Hong Kong Island in 1841 as the spoils of the first Opium War, later adding Kowloon in 1860, and the New Territories on a 99 year lease in 1898. From the very beginning it became a place of immigrants, with Chinese escaping imperial rule north of the border, and foreigners flocking to the Far East to seek their fortune (indeed, this has never changed, in the late 1980s the phrase ‘FILTH’ - Failed in London, Try Hong Kong - was coined).

Some people passed through, others ended up staying for generations, with the likes of Parsees, Mizrahi Jews, Sikhs and Gurkhas among the early foreign arrivals to make their mark, founding iconic businesses like the Star Ferry and Peninsula Hotel, and serving as the territory’s police and army. In recent years they have been supplanted in the hundreds of thousands by Filipino and Indonesian helpers (currently numbering 5% of the city’s population, with ethnic minorities altogether making up around 8% of the total). Somewhere in the mix were expat families like mine, tied to Hong Kong through work and opportunity, but always with one eye on eventually going ‘home’.

However, the concept of home has long been confused by the status of most Hong Kongers. There are various strata of residents in the city. You have the new arrivals on work permits, who have ID cards but no belonging status; once the job is over, they either find another or leave. Then you have those who have lived for seven years in Hong Kong, and applied for Permanent Residency. This is essentially citizenship, and entitles you to ‘live, study and work without any restriction’, including access to free healthcare and education, and allows you to travel to Macau (and also Albania for a stay of up to 90 days, I discovered while researching this piece!) with just your Hong Kong ID card. The caveat is you cannot stay outside Hong Kong for more than three years at a time, otherwise you’re downgraded to the less attractive ‘Right to Land’.

What it means is that you can hold a foreign passport (I have a British one), and be a Permanent Resident, meaning you get the best of both worlds (though it gets more complicated if you’re ethnic Chinese, and if you or your parents were born in Hong Kong). Then there is also a Hong Kong SAR passport, which is generally only issued to ethnic Chinese but not exclusively - notable exceptions have been former civil servant Mike Rowse, the man who brought Disneyland to Hong Kong, and the founder of Lan Kwai Fong Allan Zeman, who renounced his Canadian passport for a Hong Kong one.

Of course, not everyone has been ready to do that, which is why the largest group of Canadians outside Canada can be found in the city - a population numbering almost 300,000. Indeed, a large number of Hong Kongers like me have Permanent Residency and foreign passports, including the 5.4 million out of a population of 7.5 million who are eligible for the special British National Overseas - popularly known as the BNO - passport, and were provided with a pathway to full British citizenship as of 31 January 2021 (while I don’t have a BNO passport, I am also - as well as being a full UK national - a British Dependent Territories Citizen, at least a nice stamped certificate says so).

All in all, it’s such a state of affairs (and I hope you’ve been able to keep track), that it’s no wonder so many of us have had trouble defining our identity. But herein lies the rub. As recent years have seen the city rocked by pro-democracy protests, the once beloved city police force known as ‘Asia’s Finest’ turned into a strong-arm of the government (and reminiscent of the mainland’s People’s Armed Police), and the wishes of a majority of Hong Kongers trampled by direct intervention from Beijing, the diverse people of a city founded by immigrants have bonded as never before. For out of the fear of repression, the possible loss of our unique characteristics, and the determination of a Chinese leadership to impose their way on a people that don’t want it, has come a renewed sense of optimism, and a sense of shared destiny.

On 23 August 2019, a lifetime ago it seems now, tens of thousands of Hong Kongers joined hands in a phone-lit, night time 50 kilometer chain spread across the city, that stretched to the top of the Lion Rock, a symbolic outcrop that overlooks the Kowloon peninsula, and Hong Kong island beyond. It was called the ‘Hong Kong Way’ after the Baltic version that heralded the end of Soviet rule in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania more than three decades years ago. While those lights may have been extinguished for now, they reawakened in me the sense of pride, support and belonging I’d felt in 1989.

Yes, I was raised as a privileged child of a British elite, the offspring of a civil servant in a colony whose time was up. But, just like my parents before me who went for three years and stayed for 25, this British-born kid ended up finding a place to call home. For no matter what lies in the city’s future, I am - and forever will be - a Hong Konger.

This was a nice article and reminded me of my younger days in HK. Thanks for sharing.

It seems our identity changes over time and I have been seriously asking myself Who am I for the past 2 years. As we grow older and hopefully wiser our identity changes.

But until we are deeply rooted, we won’t know that we are essentially divine beings just experiencing the beauty and lessons of this planet.

I do miss HK.