Forever Shanghaied

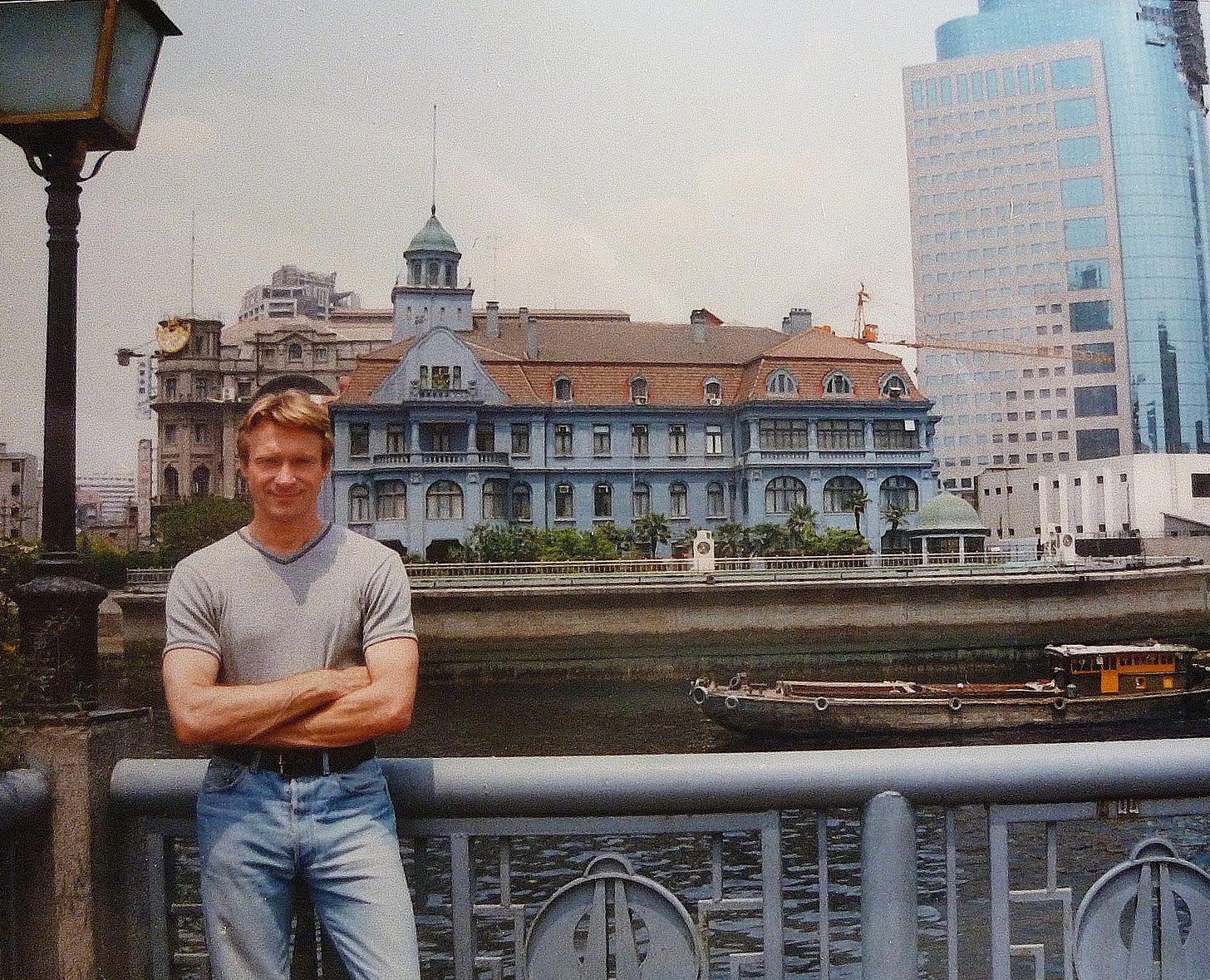

In 1992, former chartered engineer Ben Zabulis visited Shanghai (in fact, China) for the first time, a trip of exploration that began a lifelong love for the 'City of Devils'

The scene: 1992, a hot and sticky August in the city.

Shortly after arrival, and pleased with the way things had turned out, I was savouring a moment's calm and soothing cup of oolong in a plain yet comfortable hotel room when a gentle, barely audible series of taps at the door stirred my peaceful reverie.

How unusual, I thought. Who the devil could that be?

A quick peek through the fish-eye spyglass revealed not a soul. So, warily, as this was indeed a city with a somewhat racy reputation, I opened the door gingerly, expecting to discover the caller had either hightailed it or, draped salaciously across the reveal, a seamy siren, flaunting slit-to-the-waist cheongsam, intent on initiating business forthwith.

One’s imagination could at this point have run wild, as neither of these scenarios in fact manifested. Instead, my attention was drawn instantly downward to a small, round-faced Chinese boy of, I would guess, no more than six years old.

Possessed of truly impish demeanour, ‘Welcome to Shanghai!’ my caller yelled in pleasantly accented English before turning on the spot and running back, breathless, under the adoring gaze of his kindly-looking parents, occupants of the room directly across the lift lobby.

My presence had clearly been noted. Nodding my appreciation and glowing warmly within, I closed the door gently behind me. A plain hotel room had suddenly transformed. From that moment on, something told me I was going to like Shanghai. Had they guessed it was my first-ever trip to China proper? Doubtless I looked a tad green and in desperate need of reassurance.

They'd have been right too. This was a sprawling metropolis, and, what's more, I'd yet to accumulate any meaningful language skills, having only weeks earlier taken up a job in Hong Kong. Of course, such anxiety could so easily have been tempered by joining an organised tour, but, me being me, a more feral approach was preferred, though such wanton independence didn’t always sit well with the relevant authorities.

And so, smiling inwardly and indeed feeling a little reassured, I regained my reverie. It had been a morning fraught with anxious clock-watching — itching to knock off work early, scrambling to the airport, and arriving, heart in mouth, only several minutes prior to check-in closing. But I made it.

Well, despite its reputation for being noisy, frenetic and more than a little crazy, not to mention a place that more rational travellers might avoid like the plague, what on earth was I doing in Shanghai, I hear you ask?

To be honest, the city, or its notoriety at least, had long held a certain allure. For starters, few place names — if any? — can be so neatly verbed, especially to one with such unsavoury, yet riveting, undertones. As an impressionable adolescent, therefore, the notion of being shanghaied in Shanghai conjured up a certain swashbuckling menace.

Growing older, I learnt of the deliciously sleazy, seedier side of the conurbation's fleshpots, the unending parties, the hedonism, the tumult, and the intrigue therein. But, much later, as an enthusiast and professional contributor to the built environment, it was the remarkably varied architecture and infrastructure that drew me in.

Combine all that, and you have the makings of a great adventure — or pilgrimage, in my case. Even on first impressions, I couldn't help but discern a history-laden ambience where the unreserved Zeitgeist of a golden era, the aspiringly hopeful post-Great War generation, permeated throughout; perhaps, I fancifully wondered, it drove the city still. Clearly, in my mind, the place held a certain glamour. So much, it seemed, belonged to the 1920s and ‘30s, woven tightly into the fabric; you could almost smell it, almost feel it.

For me then, Shanghai's attractions lay slightly intangible, possibly even ethereal, for a beguiling genius loci — I would soon discover — pervaded its lesser-searched-out nooks and crannies where forgotten stonework, streets, and gardens abound. What secret histories, I mused, might be embodied within those settings? I suspected epic tomes aching to break loose — a wealth of facts and hearsay — if only they could be set free.

Indeed, such perambulations of the back lanes and alleyways — my particular grail — would prove a richly rewarding experience, especially away from the commercial centre. And especially away from the waterfront edifice known as the Bund, a foreign enterprise — an intrusion, some might argue — alongside the teeming, dun-coloured waters of the Huangpu River. A development that epitomises the early-19th-century powerhouse of Western dealers, optimisers of trade and profit, eventually ousted by either a world war, a civil war, or a people’s republic.

Yet, those imposing masonry palaces survive, perfectly intact — finely crafted monuments to an era most grand, and a capitalist one at that. Doubtless, built with conviction, built to last. Think Neo-Classical, think Art Deco, think Liverpool waterfront, but on a much grander scale, and you get the idea. Although repurposed later as a base for various state bureaus and hotels, the Bund had remained a hugely popular tourist attraction and promenade.

This became blatantly clear when, basking in that granite-tinged hangover of colonial ambiance, I joined the predominantly Chinese visitors to walk in the shadow of this incongruous landmark. Camera shutters clicked as we all snapped feverishly away.

I wondered what my touring cohort made of this cultural paradox: a sort of little England in Shanghai, a quirk of history. It must have been quite something for those from the more pastoral districts who, in all likelihood, had never seen anything quite like it. Then again, I'm not sure I had either, despite having pored over numerous architectural photographs showcasing the locale.

Could they — the thought struck me — have considered themselves, at that precise moment, to be treading sublimely on hallowed ground? I did; I sensed it. Though sublimely a big ask, thanks to the municipal engineering bureau jackhammering out the adjacent roads and pavements in the name of waterfront enhancement. Never mind.

Yet, jarring din aside, and with little encouragement, I could easily picture, swirling languidly around those lofty Ionic columns, the spirits of long-forgotten merchants and mariners gaping, disbelievingly, down from above. Yes, they might very well have thought, has it really sunk to this? ‘Fraid so, chaps; powerful traders no more, but the tourists still adore you.

A couple of hours passed pleasantly, but, leaving behind those handsomely scrolled granite domes and porticos, I embarked upon a detour, a mission if you like, heading west, clutching only a crude paper map, in search of that lesser-known, lesser-frequented hinterland.

It was quite a job too, pushing not only against energy-sapping sultriness on an overcast and windless day but also threading my way purposefully through the throng. A sea of inscrutable Chinese faces in my direction, difficult to read, so many, heaving to and fro. At times it felt like I was up against the whole of Shanghai.

And it was busy, an enormous swathe of mercantile activity. A commotion that could easily overwhelm. Not at all threatening, however, as people went around entirely indifferent to me. It was mesmerising more than anything else.

If lacking an explorer's prowess, I could imagine sensitive nerve ends effortlessly tormented. Enough to have the faint-hearted running for sanctuary, or the nearest bar at least. Not me, though; feeling properly reassured, the little boy's welcome had won the day, and, as big city welcomes go, it couldn't get any better than that.

Taking a moment to people-watch, it occurred to me how smartly dressed the majority were. Open-necked shirts and trousers or bright summer dresses, neatly pressed, delightfully worn too. Forever along the road to sophistication, it appeared that Shanghai's more casual Western-style attire had held the fabled, though drab, Mao suit in definite retreat.

Traffic comprised a never-ending flow of bicycles, rickshaws, soot-belching trucks, taxis of dubious roadworthiness and tired old trolley buses, all packed to heaving with comrades on their way to or from the work unit, presumably. An unstoppable force, convincingly so. Crossing the busy roads proved more than hazardous, and, consequently, the elevated pedestrian walkways were very well utilised and undoubtedly spared countless injuries, if not lives.

Captivated by the everyday scenes unfolding, a saunter down Nanjing Lu, the main shopping street at that time, instantly bestowed upon the uninitiated the sights, sounds, and smells of urban China. Frenetic would describe it well; fulfilling one major expectation at least, it was exactly how I imagined Shanghai to function. Overhead, gaudily coloured billboards, some familiar Western brands included, threw a sharp, oddly capitalist relief upon the city's stony greyness.

I was traversing what, a century or so ago, would have been the International Settlement, established and governed mainly by the British when they held sway. The architecture was therefore very much in that style with, save for a few oriental embellishments, little trace of the vernacular and, perhaps, little thought as to how these constructions might blend in.

For here stood commercial buildings of several stories, designed to appear impressive; this they effortlessly achieved and were certainly on par with those of any European city centre. Standing beside a few one-time dens of inequity put me in mind of the heyday glitz, the gaiety, the dissonant riffs of a trad jazz band, and, of course, the attendees: the decadent, the fast, the derelict — a delightful proposition — secreted behind such imposing facades. Fun parties, usurped now by a grinding urban drone, the soundtrack of modern Shanghai. Ah well, times have changed, but at least the essence remains.

Further inland and doing a roaring trade stood lesser, ramshackle brick buildings housing quaint family restaurants, tea rooms, shoe shops, booksellers, provision stores and aroma-rich bakeries. Enticed in, I refuelled on a stodgy mooncake; it was that time of year.

Also, tenements and courtyards — humble and charming — to which the majority of visitors might slip unknowingly by. But, no grand monuments to be seen; only decades of crumbling dishevelment, delightfully worn too. Age and the elements had done their work.

Granted, such sites were less prominent, difficult to spot, and invisible on the tourist map. Anonymous. Nevertheless, they were ripe for unearthing. Hidden, neglected, and considerably frayed at the edges, you might say. I would stumble upon them more by luck than direction.

Eventually, after a hard slog of around three miles, the hustle and bustle petered out as I entered upon a distinctly low-rise residential suburb. Exploration of the unfamiliar. Worlds apart from where I’d started out. Immeasurable calm; I even managed an over-the-shoulder glance to check the city hadn't followed. It hadn’t.

Barely any motor vehicles to be seen, mainly pedestrians and a few bicycles. Was this really the frenetic Shanghai of legend? It was as if the entire locale had thought better and slid willingly into an apathetic, though agreeable, torpor. A patina of weathering and unhurriedness had overlain all.

I'd half expected to encounter a more utilitarian environment, but, strangely, the entire milieu evoked sepia images of a 1930s working-class England — especially a northern one. Built by the foreign concessions, I noted row upon row of unassuming brick terraces, two or three stories, some pebble-dashed grey or stucco-coated, reddish-brown terracotta roof tiles, angular dormers, coal-burning chimney stacks, and washing strung out across lanes whilst shabbily clothed nippers frolicked in between. The last remnants of old Shanghai? Here, lay a veritable bridge to the past.

This is where, an age ago, Westerners and Chinese would have lived side by side. It was actually a nice district to wander; pavements were clear and well-formed; strikingly, a society free of vandalism and graffiti. Providing welcome shade, mature plane trees, gnarled trunks stretching to the roofline and sometimes beyond, stood regularly spaced and verdant. Nothing stirred; rich foliage weighed down by a persistant clamminess. I knew the feeling.

Strolling purposefully along, I peered inquisitively, though discreetly, through sagging casement windows and ornately fretted doors that opened directly to the pavement. Momentary glimpses into another century, another culture. Old buildings bewitch when you know where to look, understand how they fit together, and appreciate the details, the craftsmanship, and the history therein.

Poking around such places holds a certain fascination for me, no matter the country or the building type. I’ve often felt there’s a vague correlation between architectural details and lives lived, so this particular manoeuvre suited perfectly.

Was I being observed? Probably. A few passersby uttered greetings, or I think they did. But none seemed too concerned by my actions — actions I'd probably have been questioned and apprehended for elsewhere. The occasional cyclist halted, stock-still, and stared. Gentlefolk. Bright eyes, inquisitive eyes that seemingly never quite made out the stranger that stood before them.

Reassuring in one way, having always regarded myself as such, it was nice to receive confirmation from this most unlikely of sources. Strangeness indeed; as a tall, fair-haired Westerner, one never quite fitted in. I did what I do best in these situations, affected a look of innocence, and carried on. My observers followed suit.

A brief shower had meanwhile coated all surfaces with a magical sheen, which the stifling afternoon sun did its best to vaporise, similarly with the back of my shirt, though most of that due to the morning's sweaty exertion.

Almost palpable were the traditions and tales contained along these back alleys and within these simple dwellings. If only I could step inside to chat and discover stories, traditions, and how life events had forged neighbourhood folklore. Sadly, I realised that, in the time needed to muster sufficient language skills or garner the nerve for such a thing, these communities would almost certainly have vanished. You could almost hear the clock ticking. The city had entered upon an era of rapid change.

I found myself enveloped by the sounds and sensations of suburban domesticity. The sizzling of a wok, escaping through a cracked-open window, came the mouth-watering aroma of garlic, ginger and bean sprouts.

From others came incense and, I easily imagined, secret histories, unformed paragraphs and pages disappearing into the ether. Lost in translation, definitely, but in my mind I was collecting and building details, house by house.

From those open windows I could also picture the spirits of long-departed ancestors doing something similar, like light escaping to join both worlds. Ghostly drifts. Far from those wafting around the Bund columns, I envisaged these to be more humble, of few words, of few shadows, only a calming presence to those they'd left behind.

Oddly, the more I wandered, the more I gained an intense feeling of belonging, familiarity, or perhaps a vague attachment to something that was fast slipping away. Absurd, I know, walking through the past, occupying the fringes only. Another cultural paradox: seeing but never quite knowing. But that was neither here nor there; in an uncaring world, much would soon be gone, history erased.

Evidently, I was touching on the heart and soul of the suburbs. Homes, occupants, and lifestyles were calling to my inner being, faint murmurs from a bygone era. Was it my imagination, or did I really discern a vibe?

At this point, a more adept writer might have woven urban feng shui or qi vitality into the narrative. But not me; no, it would surely come across as a tad precious. Fanciful ramblings, at their best. Nonetheless, for all that, something aroused within, a stirring of sorts, enough to evoke one of those magic moments that can often touch the solo traveller when least expected.

And so it was, a perfect evening with shadows lengthening, a whiff of joss drifting on the breeze, lanterns lit, wedges of light, hushed conversations, and a cycle bell tinkling from behind. The atmosphere emanating on this late afternoon demanded attention, demanded savouring, and demanded committing to memory. I did. Standing a while, I drank it all in. A magic moment, for sure.

Thus, a fulfilling day drew to a close, with dusk encroaching, and mission accomplished, it was time to move on.

Imbued, thankfully, with a reasonable sense of direction, though exhausted and with darkness falling fast, I'd route marched a few more miles over a fairly extensive backstreet arc to emerge once more on to the Bund. Although the hordes remained, the waterfront facades now stood softly floodlit in a way that was pleasingly respectful: dignified, not Disneyfied. Thank you, municipal engineers; your morning’s jackhammering instantly forgiven.

Nearing the hotel and its neon-lit surroundings, another great blast of the city's heart and soul suddenly struck. I found myself indulging in a few beers at a simple streetside eatery. In fact, a group of five youngish men, white-collar workers, had literally shanghaied my return stroll, imploring that I join their modest, if slightly inebriated, after-work gathering. Well, why not? A chance to rest one's weary dogs, coupled with a welcome alcoholic release, seemed just the ticket after an exhausting day's unravelling of history, not to mention the chasing of a few imaginary ghosts.

Actually, I was quite taken aback. It's worth mentioning that China was a very different place back then. Mass tourism abroad had yet to be sanctioned, and, consequently, for many, direct engagement with foreigners remained a rarity. Nevertheless, an innocent curiosity existed. In general, a figurative Great Wall divided us, and contact, though not expressly forbidden, was not exactly encouraged either.

Even our means of exchange differed: specially issued certificates — toy money, you could say — for tourists and local yuan for citizens. Fine if restricting oneself to government-endorsed establishments (the ubiquitous Friendship Store, for example), but a no-no if wishing to patronise — illegally — the smaller, independent shops or stalls.

Although toy money in our eyes, for the locals, such certificates constituted a means to much-desired hard currency. And so, away from prying eyes, usually in a shaded doorway or a convenient convenience, a somewhat surreptitious black-market swap would facilitate the necessary solution. Though I hasten to add — your sniggers sensed even from here — this is the only type of trading I have ever conducted in a public loo.

With little choice then, I sat gladly amongst my newfound friends despite their inability to speak a word of English and my Mandarin, at that time limited to hao (good), cai (vegetable), and fan (cooked rice). Wisely, before arriving, principally to avoid starvation, I figured that if all else failed, armed with this simple vocab, I should at least be able to order rice and vegetables — or, going one better, good rice and vegetables — at any chosen restaurant.

Aside from some erratic sign language, my contribution to the conversation, it goes without saying, consisted solely of addressing the quality of food on offer. Nonetheless, an hour or so of incomprehensible frivolity passed pleasantly, though blurrily — a surreal moment as if caught in slow motion with the city racing past.

Eventually, the time came for us all to drift off, and, bidding goodnight, I was released without charge. Quite literally, as it happened, my hosts accepted not a single yuan in recompense; now I knew I liked Shanghai and henceforth promised, from that moment onwards, to spare no effort in learning Mandarin — it seems I’d unwittingly started.

Amazingly, I reached my hotel room in one piece and fell swiftly asleep. For big-city exploration is a tiring affair, and the next day would yield yet more of the same, shanghaied or not.

And so, the curtains closed on day one of my first ever visit, and, as you’ve no doubt twigged, Shanghai did not disappoint. I loved it all. It was everything I'd expected and more. Granted, not the most attractive of places, even by Chinese standards, but it scored highly on style, abandoned corners, and tiny nests of intrigue, lots of them too. There's an indefinable edge to all that city, a personality to be detected, a warmth even.

Incidentally, I’m not sure I picked up directly on any of those secret histories or epic tomes aching to break loose that I initially hoped to discover, a bit whimsical and far-fetched perhaps. Or maybe I’d simply tuned in to the wrong frequency. But I did glean, insofar as anyone can on such a condensed investigation, a basic understanding, a valuable insight, as to how people lived back then, and some still do, for that matter.

Well, fast-forward thirty-odd years, and, following several more visits and kept promises in the form of painful ad hoc language instruction, my ability to chinwag in the local patois flourishes — well, comparatively at least. Although communication had much improved, I never did get around, regrettably, to visiting any of those old houses for a nice cup of cha and a friendly chat.

As expected, urban development had occurred, both rampant and spectacular. Sadly, the dreaded gentrification saw family shops and businesses effortlessly subsumed by the dominant multinationals. A significant loss, the street ambiance would never quite be the same. Yes, I know; it's happening the world over, unfortunately.

Funnily enough, although some of the places I'd explored back then had long gone, Shanghai, even in its current modernistic reincarnation, still attracts. It never quite lets me go: I seem forever destined to return. They say the places we travel to aren't always random, that we are often drawn to those that engage some quality within ourselves. If so, Shanghai does it for me.

By the way, full marks to the municipal engineers who eventually completed their enhancement work — a wonderful job, too — and the Bund has become an even greater joy to stroll.

Sadly, though predictably, I never bumped into the ‘Shanghai Five’ again, and, consequently, I pray their generosity will be, or has been, rewarded in heaven. I toast them, even now.

Furthermore, I often think of that welcoming little boy whose infectious enthusiasm touched me greatly that day. A moment I now regard as my official welcome to Shanghai, and indeed China as a whole.

I have difficulty grappling with the idea that he would now be pushing forty — how time flies — an adult with his own children, most likely. I wonder if he'd ever recognise himself should he come across this passage one day — it would be nice to think so.

Great article. I first made it to Shanghai in 1997 - retracing the footsteps of 2 grand uncles who served in the shanghai Municipal Police in the 1929s.

The article does a great job of capturing the vibe of the city before it became the high tech metropolis it is today.

Great pictures! I was also in China in the late nineties but I don't have a digital version of the pictures I took. I think I also did not took so many as I was living there and after a while it was not a novelty anymore.