A Photo of Life and Death

On 17 April 1975, young French photographer Roland Neveu found himself on the streets of Phnom Penh as the Khmer Rouge made their final push on the capital

When the time comes, and you have to run for your life, what would you take? I’ve often thought about that question, but especially so since I first saw the above photo, one of the many stunning images from photographer Roland Neveu’s impressive book The Fall of Phnom Penh, which covers the events of 17 April 1975, some 45 years ago.

The 24 year-old Neveu had only recently arrived back in Cambodia, having spent the previous two years completing the required military service in his French homeland. He hadn’t arrived with much, but was armed with a camera, a few rolls of film, and - most importantly - a contact at the prestigious Gamma photo agency in Paris, home to other war photographers like Gilles Caron, Catherine Leroy and Françoise Demulder.

April has always been an important month in Indochina, heralding the end of the dry season and beginning of the wet. For more than five years it had also been a signifier of the struggle to and fro between government and Khmer Rouge forces, as the former made advances when the weather was good, only to be beaten back as torrential rains gave the adaptable guerrillas the advantage over the more technically sophisticated equipment of the regime. In April 1975 however, the writing was on the wall for the defenders of the capital, one of the last redoubts of the US-backed Lon Nol forces.

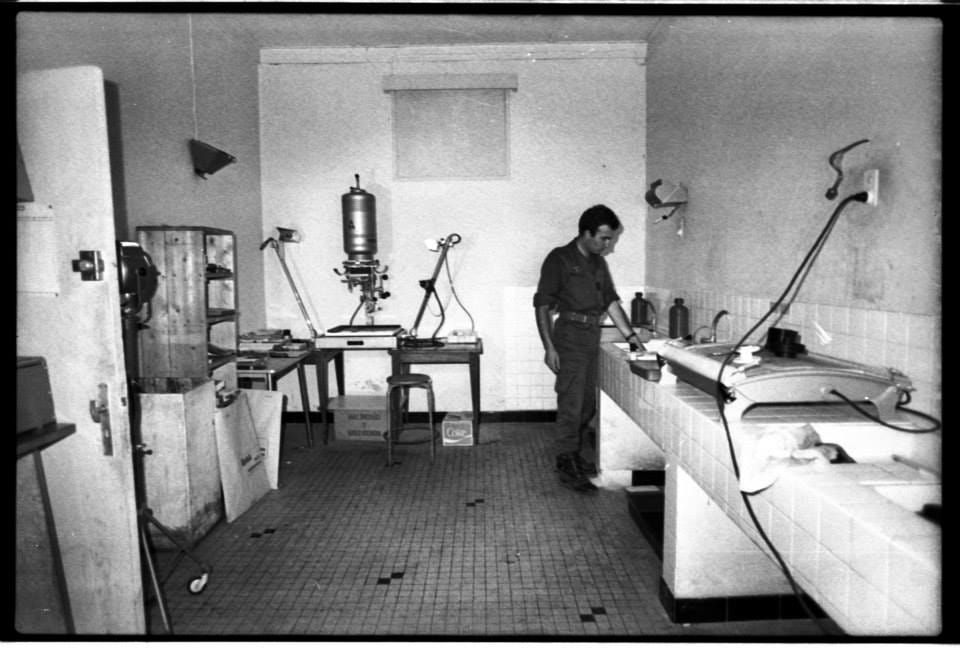

Roland’s photo lab while completing his military service in the south of France (Pau), 1973

“I had an idea that things were going to end soon,” says Neveu over the phone from his apartment in Bangkok, the city he has called home for the last 30 years and where he is currently hunkered down in self-isolation. “The change of seasons, the shrinking space occupied by the government, and the claws of the Khmer Rouge tightening their grip.” He recalls people were streaming into the city, fleeing from the advancing army, and evacuating the refugee camps that had encircled Phnom Penh for miles. The number of people in the capital had ballooned to more than 2 million - remarkably, a figure that is only slightly less than today’s population. “People were just living on the street, making their homes out of cardboard boxes, whatever they could find,” recalls Neveu.

Despite the obvious panic in the surrounding countryside, information on what exactly was happening was hard to come by for the young French photographer. “We didn’t have information circulating instantly like we do now,” he says, “so we couldn’t easily find out what was going on.” With phone lines down, he instead relied upon a network of reliable sources, regularly visiting the French embassy and hanging out at popular journalist gathering spots like the Hotel Le Royal, now better known locally as Raffles.

Neveu had to plan his day accordingly, moving throughout the city in order to follow the story. It didn’t help that the government had set a 24 hour curfew, although the situation was such that not many were paying attention to it. A more pressing matter was finding necessities when most shops and markets were closed. “You can go a long time without food when you’re young,” laughs Neveu, “but you have to eat some time!” He was also mainly on foot, with cars scarce, local cyclos just as hard to find, and his rented motorbike reclaimed by its owner. Necessity being the mother of invention, he found that through walking he ended up getting more photos of life on the streets.

Eventually returning to his hotel, the Sukhalay located close to the landmark Art Deco Central Market, he found it almost deserted. Waking the next day, everyone was gone, and the local coffee stall where he sat every morning was closed. He packed up and headed for the French embassy, as close to the frontlines as he dared. As night fell, he could see smoke over Tuol Kork, as forces battled for control of the power station and TV antennae, and heard gunshots and explosions from Route 5, the riverside highway that gave the advancing Khmer Rouge a direct route south into the heart of the city.

Roland riding in a truck with celebrating soldiers through Phnom Penh, 17 April 1975

Waking early, around 6am, he poked his head outside of the embassy compound to see what was going on, when a soldier came running by. With barely enough time to raise his camera, “I had a 30th of a second at f/2”, he snapped a shot of a young Cambodian government soldier fleeing the fighting, running as fast as he could towards the city, with a gun in one hand, guitar in the other. “It was obvious this was the last shootout,” remembers Neveu, “it was the final end of the game, and everything died after that.”

As the sun rose higher, he spent the morning wandering the city, taking photos of the victorious Khmer Rouge soldiers and the celebrating populace, most just relieved the fighting had stopped, and with no idea of the horrors to come over the next four years. “As the day grew the mood was changing,” remarks Neveu, “but we were so busy and it was so hot that we didn’t have time to stop and think, and we certainly never thought that Phnom Penh would be emptied.” He wandered far to the south, encountering other foreigners recording the moment, including a French teacher he knew, whose camera had just been confiscated by the guerillas. It was a warning that perhaps it was time to return to the relative safety of the French embassy, where he carefully put aside a few rolls of film, so he’d be ready to shoot the next day - though that day never came.

The Khmer Rouge had announced that the United States was going to bomb the city, so people needed to pack just their essential belongings and go to the countryside for a few days, after which they could return home. It was of course a terrible ruse, a way to have two million people willingly leave the safety of their homes and walk away from their lives. Many never came back. For three long weeks, Neveu and almost all of the foreigners left in Phnom Penh remained trapped in the embassy, the occasional plane overhead briefly giving hope they’d be flown out. Finally, soldiers arrived with a fleet of trucks, and they went in convoy on a rough three day ride to the Thai border. “We didn’t see any people along the entire journey,” Neveu remembers, “not even when we stopped in Battambang for the night - not a soul. The Khmer Rouge had cleared the entire route, hiding the dead bodies, and making sure we didn't encounter anyone.”

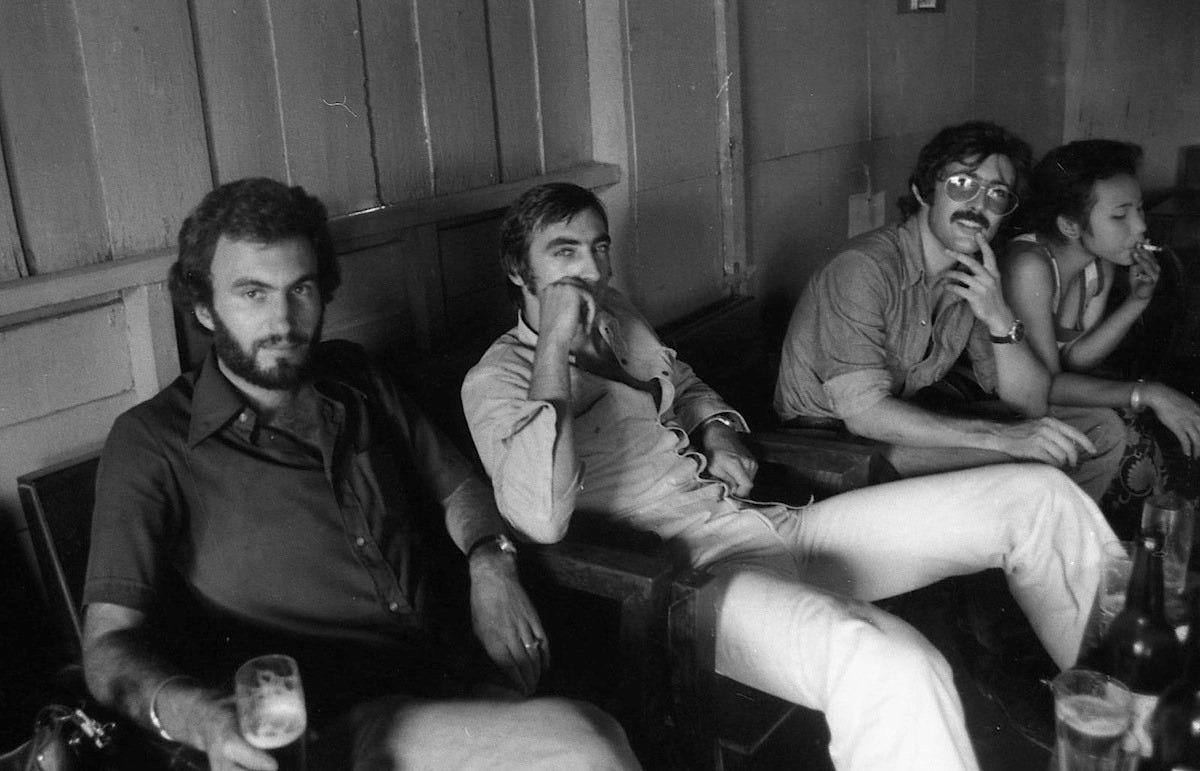

Roland (far left) in Vientiane, June 1975, with Alain Streicher and Stan Boiffin-Vivier

After a final search by their captors, who still did not find the film he had hidden on his body, they finally walked over the border at Poipet, into the arms of the waiting Thai authorities and French embassy staff. After being driven to Bangkok, they were put on a plane to Paris, and home. But Neveu’s story did not end there - three weeks later he was headed to Laos to cover that country’s unfolding civil war, his coverage of the fall of Phnom Penh beginning a storied career as a photojournalist. “I was 25 years old,” says Neveu with a smile. “At that age you don’t really think, you just go. You also don’t think too much about what is happening around, you just get on with the job.”

Remarkably, it was months before he saw most of the images he took of that fateful April day, the undeveloped rolls of film sent directly to Gamma in Paris for processing. So how did he know he had the shots? “When you press the shutter you just know that you have the picture, you know you have captured the truth of what you see.” For the world, that horrible truth wouldn’t reveal itself until the downfall of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, but through his photos, Neveu preserved the events of 17 April 1975 forever.

25 years old. The fortune of youth on his side …

Amazing story, amazing times ! What a different place Southeast Asia, and indeed the world, was back then, an enticing mix of excitement and danger. A pleasant reminder also of how we used and processed film, I have to admit to missing that, not to mention the sound and satisfaction at the end of a shoot and the roll rewinding !